The Stage is Set

Interview with Carla Haslbauer, author and illustrator of My Mother’s Delightful Deaths

Carla Haslbauer is an illustrator who was born near Frankfurt, Germany but for the last few years has lived in Lucerne, Switzerland. My Mother’s Delightful Deaths, published by NorthSouth Books in fall of 2021, is her first children’s book. In this conversation, Haslbauer tells how her first children’s story came about, how picture books and comic strips complement each other, and why when she was younger she was often hugged by “strange women.”

Your mother is an opera singer and is the central figure in your story. Will you tell us how much truth there is in the fiction?

Quite a lot! Some of the illustrations are simply scenes I remember from when I was a child. It really did happen that neighbors would ring the doorbell when my mother had just sung a particularly high note—because they were worried about her. Especially those who didn’t know much about opera. It also happened quite frequently that I didn’t recognize her myself when she was wearing a costume or a wig. Then I was scared stiff of this strange woman who kept wanting to kiss me! Those are very real memories from childhood.

Was it sometimes difficult to relive such aspects of your childhood?

On the one hand, it’s lovely to be able to use these childhood memories creatively and make a story out of them. But on the other, it’s difficult to achieve a proper degree of detachment, because I didn’t want to create direct illustrations of myself. Trying to look at my own memories from the outside was a challenge, but it was all part of the process. That’s the only way you can achieve a certain degree of freedom in order to separate yourself from yourself. I invented a character who is similar to me, but who does things differently from the way I do them.

My Mother’s Delightful Deaths grew out of your graduation project. What gave you the idea in the first place?

Actually, the first thing that came to me was the title. At some time or other, I’d written it down because I wanted to make a comic strip out of all the scenes in which my mother died or was dying. When I was preparing for my BA, I skimmed through my old sketchbooks, and this title simply jumped off the page. My tutor, Pierre Thomé, liked it right from the start, and that set the ball rolling. Fortunately, the publishers never thought of changing the title.

How did your mother react to your graduation piece?

She thought it was very funny, and when she went to the exhibition hall where our graduation work was displayed, she burst out laughing. In some ways, as an opera singer my mother also tells stories. No doubt I’ve inherited part of my love of storytelling from her. In the early days, we were always making up little tales.

…as an opera singer my mother also tells stories. No doubt I’ve inherited part of my love of storytelling from her.

Carla Haslbauer

So what exactly happened? You finished your graduation piece, but later with NordSüd it changed into something quite different. How did you respond to that? And how did you make the contact in the first place?

The BA project basically wasn’t a children’s book at all but more of a hybrid between picture book and comic strip, with no particular readership in mind. Then during the graduation exhibition in 2018, one of my lecturers introduced me to Herwig Bitsche, the NordSüd publisher. Later we met again at his office and discussed whether it could be made into a children’s book. It took me a very long time to think the whole thing through, because I was urgently in need of a break after working so long and so intensively on the project. But in the end it was clear to me: I did want to make it into a children’s book.

What more can you tell us about the process of turning a graduation project into a children’s book?

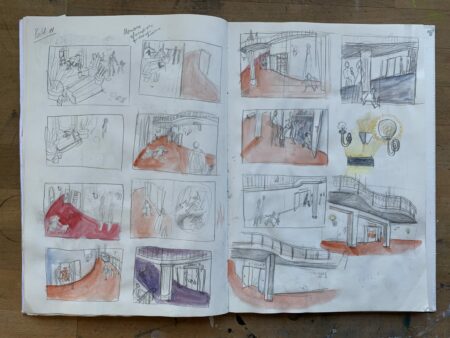

I created several storyboards based on the original version. In other words, I tried new approaches relating to the content. For it to work as a children’s book, the story had to have a new narrative structure, and also it had to be compressed into 48 pages. That meant dropping some pictures and creating new ones. The end product is a colorful mixture of new and old. There are also some old ones that I reworked so that they fit in better with the new ones. Above all, though, I learned about certain purely formal matters like endpapers, blurbs, and the fact that the number of pages must be divisible by 16 because of the way the sheets of paper are folded.

How did you set about designing the illustrations?

For the illustration that shows people arriving at the opera, I drew several sketches just to get the right perspective for the entrance hall. I tried it this way and that, the different directions in which people were walking, with or against the flow of the text. At the same time, I wanted to capture the curve of the wall. Even the position of the text plays its part—obviously I know that from the work I’ve done with comics. So a lot of thought goes into the actual composition of the picture. I used different photos of the theater in Lucerne as my model. And especially with the later pictures, I drew several preliminary studies—for instance, of the family’s furniture, because such objects tell you a lot about the character and the everyday life of the family.

What techniques do you use?

I do most of my sketches with a pencil. I’m not too keen on fineliner pens, because you have to be so precise with them. When I’ve finished the sketching phase, I draw very lightly so that the final picture still gives the impression of spontaneity. Sometimes I plan the individual steps in detail, for instance by sticking bits of paper over those parts of the picture where I don’t want any ground. Then for the coloring, I prefer to use watercolors and crayons. I do lettering and speech bubbles separately, and then I scan them and reduce them digitally. But I do a minimal amount of digital reworking. Most of the time, I just touch up little smudges and correct the colors because they tend to fade a little when they’re scanned. Getting from the final sketches to the finished picture takes about four hours, not including corrections.

You also do a lot in the field of comics, and you’re a member of the Corner Collective. What do you see as the most important differences between comics and picture books?

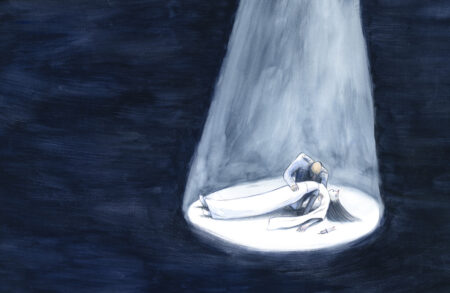

For comics I tend to work more with watercolor and sometimes also fineliners, because there’s so much text, and it needs to be easy to read. If I used pencils, there would be a visual clash, because they are different shades of gray. With comics I like the way the narrative proceeds in panels, whereas in picture books it depends more on turning the pages. My work for comics is more spontaneous and direct, whereas a picture book leaves room for dreaminess and imagination, and also makes greater use of space. With large-scale pictures, I think it’s important to guide the reader’s eye. The center is more finished, and the peripheral areas can be more like sketches, drawn with just a few lines. The fact that these pictures are no less expressive is perhaps thanks to my experience with comics. The book also contains little tributes to the comic form, for example one page with vignettes, and of course speech bubbles with handwritten lettering.

Where does your inspiration come from?

I get most of my ideas when I’m out walking—which I love doing. The hunting instinct that I feel then is sometimes almost painful. But what drives me to start drawing is always the stories behind the objects. The picture that emerges then has little to do with the reality. And what I want to depict is emphatically not the reality but how I see the reality. By drawing something in my own style, I can identify much more closely with it. Drawing is what you might call my access to reality.

Would you like to create more children’s books?

Definitely. I’d really like to do one about fish and the underwater world. But there are also more stories from my childhood lying dormant in me. In addition to my mother, there’s my father. He’s a doctor, but he’s also a writer. There’s enough material there for a sequel. So perhaps one day the deaths of my mother will be followed by the lives of my father.