Musical Makings

Interview with Wiebke Rauers and Kai Lüftner, the artists behind Jitterbug

With Jitterbug, the illustrator Wiebke Rauers and the author Kai Lüftner have combined their creative talents to produce a children’s book for NorthSouth. In Jitterbug, Marie is not your normal, well-behaved ladybug, because her heart beats to the rhythm of rock ‘n’ roll. Her music is ear-splitting, with voice and electric guitar always at full volume, and at first it gets on everyone’s nerves. But in the end, the whole meadow is rocking and rolling with her. Julia Ann Stüssi with NordSüd Verlag talked to Wiebke and Kai about their collaboration and their new book. David Henry Wilson translated the interview.

Where are you at the moment?

Kai: I’m on the Danish island of Bornholm. We moved here from Berlin two and a half years ago. And I’ve just commandeered the top floor for my workplace. It’s nice and cosy…and I’ve also got a better network connection here than I had for fifteen years in Berlin.

Wiebke: I’m in my living room in Berlin – my partner and I have always worked at home. Our daughter has taken over the tiny room we used to use as our studio, and so we’ve moved into the living room. My partner sits right next to me – our desks are adjacent, and when we’ve got our headphones on, neither of us can hear the phone ring.

What do you need for your work?

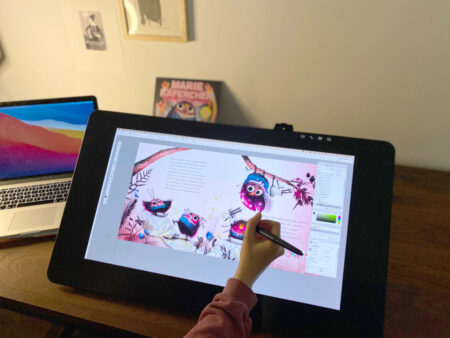

Wiebke: My wonderful Cintiq drawing tablet, my computer, and music. I can’t do anything without music.

Kai: I also like to have headphones on and listen to music, but I can’t stand it if there’s someone sitting next to me. The most important thing for me is peace and quiet, which is why I’m so happy up here. I’ve got a fantastic view and I can always see if someone’s coming, which gives me total control. The anonymity and the chance to focus completely on my work are worth a fortune, and they’ve made a huge difference to its quality and my efficiency.

Wiebke: It’s similar with me. I used to have a permanent job and I sat in a large open office, right at the back, so I could see everyone else. Every time someone walked past, I couldn’t help looking up. When that happens, you get distracted from the ideas you’ve just had. I always found that disturbing. Here I simply look at the wall if I look at anything at all. In fact, I’m never actually interrupted when I’m working.

What music do you listen to when you’re working?

Wiebke: Rock, or hard rock, and sometimes metal. It depends what I’m working on at the time. In any case, not what people might imagine I’d want to hear while I’m illustrating a children’s book.

So what do you think people might imagine?

Kai: Shakira!

Wiebke: Yes, maybe. Definitely something lively that puts you in a good mood. But that’s not what I need at all. I need something that drives me on. And I feel that pain and sadness can make you more creative than when everything is nice and easy. I don’t know if I would go on drawing if I emigrated to Hawaii and spent all my time lying around on the beach or surfing. On the other hand, when it’s pouring rain, it’s time to sit at your desk and get to work.

Kai: I envy Wiebke. As an illustrator she can listen to misery-making music. Actually we realized – also when we were working on Jitterbug – that we have plenty in common when it comes to our taste in music. We keep sending each other new discoveries. But although I really love hard music as hard as possible – I simply can’t listen to it while I’m working. I can’t listen to texts either, which is a shame. People who work with pictures can even listen to podcasts. But I’ve discovered some sort of alpha waves for myself, a kind of meditation stuff, instrumental alpha waves. Something between yoga and meditation, an atmosphere that helps me filter away the outside world and all its noises.

What gave you the idea for Jitterbug?

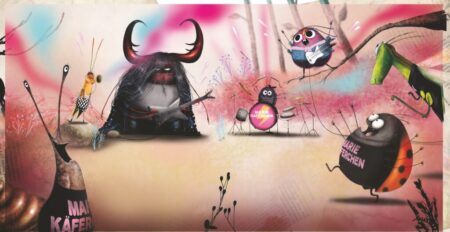

Wiebke: I can remember, Kai, that you sent me a message. Your son had found a dead ladybug, and you felt sorry. But your son just said: “Dad, that’s Marie – that’s Marie Käferchen!” And I thought: “Oh my God!” (Kai’s son had transformed the name for “ladybug” in German from Marienkaefer to Marie Käferchen, meaning “beetle called Marie.” The German title for Jitterbug is Marie Käferchen.)

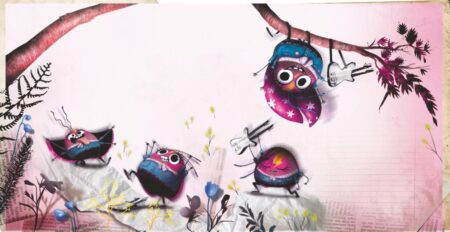

Kai: That’s exactly what happened. Many of my books have been inspired by watching children and listening to them talking. For example, I once wrote a book about death, which was sparked off by the way my son sees such things. “Look, Dad, that rat over there is dead, but it doesn’t need its body anymore.” I found it quite fascinating, that a child should view death that way. Anyway, I sent the idea of a singing, dancing ladybug to Wiebke, and half an hour later she sent me a picture of a punk rock ladybug complete with a David Bowie quiff!

I sent the idea of a singing, dancing ladybug to Wiebke, and half an hour later she sent me a picture of a punk rock ladybug complete with a David Bowie quiff!

Kai Lüftner

It’s a curse and a blessing with Wiebke and me that we do this crazy ping-ponging! Sometimes it happens so quickly that it’s like an avalanche, not just with our work on individual books, but also with the number of titles that come tumbling out of us. I’ve never experienced anything like it, though I’ve been writing for ten years now. I gaze at my surroundings, and take everything in without any sort of filtering, but I could never match the sheer drive of Wiebke’s creativity – in a moment, she can fix an idea with perfect clarity into a single picture!

How did the collaboration go on after that?

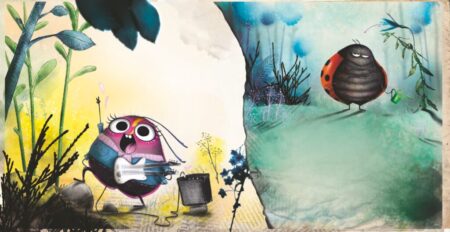

Wiebke: With Jitterbug, another half an hour, or maybe half a day went by. Then Kai recorded himself reading the whole text and sent it to me. I thought: Man, that’s crazy! And straight away I could see a picture of Marie – in her denim jacket complete with all the patches. So I sat down there and then, and drew it. That was the picture that was used for the cover. After that came more pictures of her in the world of glam rock. And then we took the whole thing to NordSüd, and there were hardly any changes to the text, were there?

Kai: To be precise, there was just one detail. No notes or questions – simply one thing. I think our editor, Andrea Naasan, changed a couple of words. Our collaboration is so efficient, so quick and so intensive…even the best craftspeople and the cleverest financiers could never get things done like that! And it wasn’t even planned. Since Wiebke and I started working together, the genre of children’s books has become incredibly exciting for me.

Wiebke, what do children’s books mean for you? Are they your favorite genre too?

Wiebke: Yes, absolutely. Even when I started at primary school, I already knew that I wanted to create children’s books. I was always good at drawing and painting, but everybody used to laugh at me. Even the teachers would smile: there was no money in that, they said. You couldn’t earn a living with such a job. I have to say that only made me all the more determined to do what I wanted to do!

I did a course that was very general, but I still knew that it was illustration that I wanted to study. So I applied to go to college in Hamburg. I was accepted, but to tell the truth, I was too lazy to go to Hamburg – I much preferred to go on living with my parents for a while longer. Then I studied communications, mainly focusing on illustration. But job openings for illustrators were still few and far between. However, a professor of photography introduced me to photograms, and I’ve used these in Jitterbug.

How do photograms work, and how did you use them in Jitterbug?

Wiebke: You take a sheet of unexposed photo paper and working in a dark room, place whatever you like on it. When exposed to light, only the uncovered aspects develop, creating areas of light and dark. For Jitterbug I used quite a lot of things from my parents’ garden – including plant material. Afterwards, I scanned it all into Photoshop and cut it out.

In my original sketches, I’d already decided that there needed to be something “real” in them, so that one would have the impression of being in a field. There had to be a third level in addition to foreground and background. The photograms in the book are black, and I worked on them afterwards – I actually painted over them to make them seem “real.” This creates a sort of plasticity. It’s a technique I’d never used before. I think it fits in perfectly with the “rock ‘n’ roll” theme. There are also newspaper snippets in the illustrations, which I scanned and worked into the background. Again, they fit in nicely with “rock ‘n’ roll.”

What makes for a good children’s book?

Wiebke: For me, a good children’s book should make not just the children but also the parents want to read it again right from the start. Twenty times!

Kai: I agree – it has to appeal to the parents as well. That sounds obvious, but it often fails to happen. When I look at the German language market, I frequently find books that are “educational,” or “politically correct,” and generally aimed at very small target groups. In Scandinavia it’s completely different. You’ve even got “punk” writers like Haldan Rasmussen and Sven Nordqvist. In English you’ve got authors like David Walliams, famous for his sketch show “Little Britain,” who writes children’s books like Gangsta Granny. They all come from different backgrounds. They come from different worlds, and they bring these into their children’s books. This makes the books what I think they used to be in the good old days: family entertainment. Entertainment that appeals to everyone.

In the realm of German language children’s books, I’ve had various discussions about whether one should write stories about children from broken homes, or whether one can use the word corpse in thrillers for children and young adults. You’re frequently made to find some sort of circumlocution. But that’s not the world of my own experience. My children are interested in such things, and I think it’s all part of their upbringing. A camping trip for example always provides rich material: there’s lovesickness, homesickness, romance, and jumping around on bunk beds. As far as I’m concerned, all of that is great material for a children’s book.

This has long been acceptable in the film world through Pixar – and it’s something I often discuss with Wiebke. Maybe children won’t catch on to every detail in a film rated suitable for all ages, but that doesn’t matter. I like to compare this to a toboggan run. When you’re a tiny kid, the slope seems scarily long and steep, and you scream your head off. Twenty years later, you go there again, and you find a gentle slope of about three percent, and it goes on for about 20 yards. I think it’s a great experience for a child to feel just a little overwhelmed, and then later with hindsight to see how relative everything is.

And I think there’s nothing worse than parents who can’t be bothered to read to their children. That really negates everything we try to achieve through literature.

I absolutely love picture books because each one is a mini-world in itself.

Wiebke Rauers

Wiebke: I absolutely love picture books because each one is a mini-world in itself. The limited number of pages means the story must be relatively short, but every page from start to finish is illustrated. This allows you to create a superfine world in its entirety. Not just visually but also through the content. If the writer and illustrator both do their job, the result is totally cool!

Kai: Yes, and we were also delighted that NordSüd not only accepted the project but also contributed to it in various ways. There are many details that children might not even notice, though parents will. For example, the David Bowie quiff and the format of the book, which will remind some grown-ups of LPs. These things are finishing touches that make the book such fun.

Wiebke, which artists do you most admire?

Wiebke: Most of them are in the field of character design and work on Pixar films. For example, Carter Goodrich, Nico Merlet, Uli Meyer – they’re unbelievably good at bringing characters to life.

Are you both familiar with Marie’s experiences? Do your passions sometimes also meet with resistance or rejection?

Kai: That’s exactly what’s come to light just now when you were talking to Wiebke! You said, Wiebke, that people laughed at you when you were doing your drawings at primary school, but you knew even then what you wanted to do. You ended up just like Marie, standing virtually alone in the field, because you went on doing your own thing. The text I wrote could have been written specially for Wiebke! She more than proved it when she responded so quickly with the perfect picture of the character. In my perception of Wiebke, and I think also in hers of me, there are deep affinities. And here’s another analogy for you: Marie has four arms, and so she can play the guitar more quickly than anyone else. Just like Wiebke: she has four hands, because she can paint so quickly.

Marie has four arms, and so she can play the guitar more quickly than anyone else. Just like Wiebke: she has four hands, because she can paint so quickly.

Kai Lüftner

There’s nothing new in writing about “outlaws” or characters who differ from the norm but believe in themselves. Especially in children’s books. But in our book, we’re playing with an extreme case: Marie is a small insect who is dressed in leather jacket and studs and rocks and rolls with a guitar and an amplifier.

Do you feel that you’ve achieved recognition, Wiebke?

Wiebke: Definitely. In the past, I was always banging my head against a brick wall, both at school and also later in the field of animation and with different publishers. They’re all so ready to criticize, although the customers – the potential buyers – aren’t at all like that. There are lots of things that the people at the top think customers won’t be interested in – for instance, particular forms of art – but that simply isn’t true. For quite a while I’ve had an Instagram account. When I post things that I’ve drawn just for my own pleasure, I get a lot of honest feedback from people who don’t know me and who come from different cultural backgrounds. And the majority [of people] are positive.

Kai: Yes, Wiebke, and you also often describe how people like to underestimate you. They see a pretty, red-haired girl who paints a bit and is actually commissioned to draw sweet little figures. They just don’t see the punk rock that lies behind it all. With me, it’s the exact opposite: what they see is a bald-headed, tattooed man who weighs 100 kilos [about 220 lbs] and is good for nothing except describing his work routine and, at best, belching and farting. They just can’t see that he has another side to him. With our Jitterbug, we explore the heights and the depths. In Wiebke I see far more than someone commissioned to create yet another sweet little character with sweetly fluttering eyelids. That is a misconception– it’s like sugar without the spice.

What’s actually missing here is the hard-as-nails, tattooed, 100-kilo beetle who…

Kai: …does ballet dancing. Exactly! We’re well ahead of you. On the subject of the hundred kilos – it’s above all the stag beetle bass guitarist in Jitterbug who clearly needs to have a story of his own…

Wiebke: Incidentally, when I was sitting looking at the line-up – that’s what we call it in animation, when we put all the characters next to one another – I asked myself what other musicians ought to be in there. I started work on the stag beetle, and initially he was quite harmless. But then I realized that somehow he didn’t fit in that way. So I changed him into what he is now in the book. I still remember my thoughts at the time: “There’s no way NordSüd will wave this through! Absolutely no way! I was sure they’d censor it. No, it’s too vulgar – the studs must go. Too black. Too metallic.” – but you folk at NordSüd thought it was absolutely brilliant. That was the decisive moment when I said to myself: I love being with you! I felt that I couldn’t be in better hands.

Kai, why did you choose to write Jitterbug in rhyme?

Kai: I’m wild about music, though I can’t play an instrument, apart from a bit of guitar. My main tool is verse – I love poetry. It’s the perfect medium for me. It’s the height of luxury to sit down and write a lengthy song. And that’s what I did in just two hours with Jitterbug. But sometimes I work all day for two or three days before I finish a project. I love the possibilities that language offers, and I love the chance to use them as a way of communicating with our target group – which is my rather prosaic name for them. I think you can have a perfectly enjoyable conversation in your local vernacular, and it doesn’t always have to be a lot of intellectual twaddle with a posh accent.

I don’t always have to write my children’s books in rhyme, but I just love doing it when I’m working with Wiebke. It works perfectly over twelve, fourteen or sixteen double pages – neatly compressed, almost like a short film, but you spend an evening reading it instead of watching it. Children’s books are often “simple,” but with poetry you can raise them to a higher level by showing more of what can be done with language. At the moment, I really can’t imagine creating rhyming texts with anyone else but Wiebke. I just wouldn’t do it – I wouldn’t feel the urge to do it! Or at least I would ask her first – always!