Nature Knocking at the Front Door

Interview with Käthi Bhend, illustrator of In My Dreams I Can Fly and A Tale of Two Brothers

Käthi Bhend’s illustrations are filled with mystery and detail: what initially seems simple, on closer inspection turns out to be well planned, refined, and tailored to her individual taste. An illustrator of international children’s books, she began her artistic career drawing illustrations for children through a different outlet: educational texts. In this interview with Pascale Blatter, Bhend relays how she entertained neighborhood children in exchange for feedback, how she made creepy crawlies kitsch, and how she answered nature knocking at her front door.

Your pictures are full of details that you might notice only with a second glance. Why do you hide so much?

First comes the plot of the story and then come the additional details: the birds, fungi, fruit, trees, and roots. Children love hidden things. And they also find them much more quickly than adults. When children realize that there are several possible stories in one picture, they keep looking at it. They feel proud when they discover something by themselves. “There it is!” Or “If I screw up my eyes, I can see . . .” A face that only appears when you turn the pages, or a tiny concealed figure, or snakes behind stones. Sometimes I also plant clues for children I know.

Arranging things so that they turn into something else, that’s also what children do. Do you feel that making pictures is like playing a game?

Many illustrators say that one has to remain a child in order to feel what children feel. But we’re also dependent on what our editors allow or don’t allow. When you make a picture book, the tricky question is, how do you guide the reader’s vision? One reads a picture book like a text. I also take care that there’s an empty space where the reader is going to hold the book.

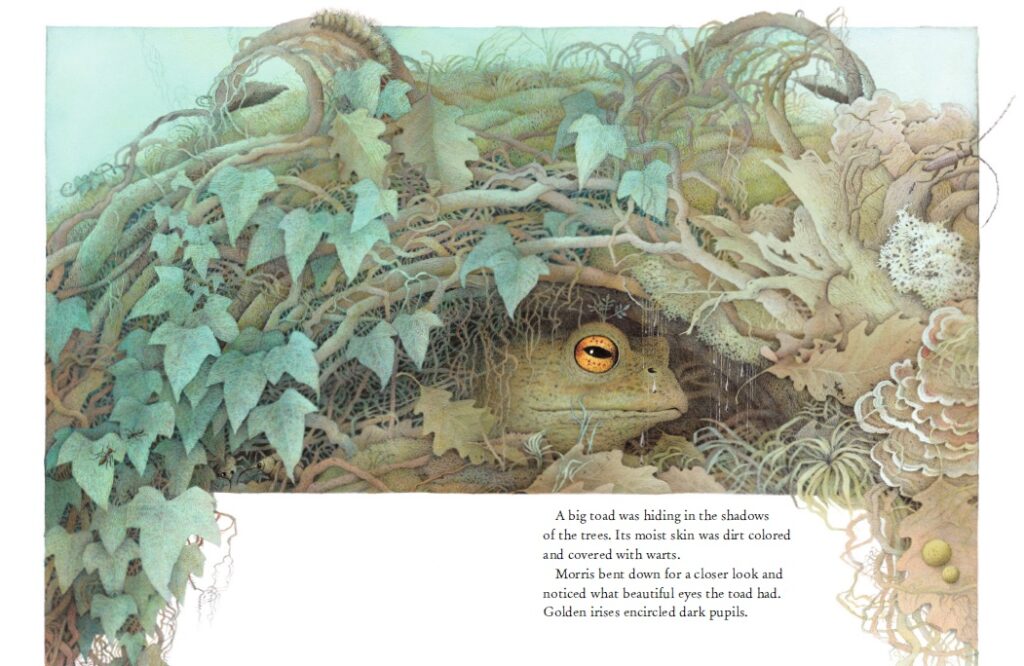

In A Tale of Two Brothers, there’s a toad in a hollow, and the hollow itself looks like a toad with all its curving leaves and branches. The different levels of your pictures can only be seen if you study them for a while. With your pictures do you try to make children look closely at things?

They do that anyway. Children have a direct way of looking at the world, so long as grown-ups don’t block it by imposing a view of their own. For my illustrations, I learned from children. My husband and I lived for thirty years in an Appenzeller farmhouse in Oberegg, and in that time fourteen children were born in the village. Their loud voices used to be my alarm clock in the morning when they went tobogganing past our house on their way to school. And they were also the public for my work. “What can you see there?” I used to ask them. Asking children is very interesting because it’s only then that you can learn what attracts their attention. I also offered them something in exchange: parties in the forest, carnival time with homemade masks, Christmas in the woods, trudging through the snow at night with candles and torches. Recently I met one of the girls in the mail bus. She’s all grown up now, but straightaway she asked, “Do you remember how we used to walk through the woods with candles?”

Your husband comes from Zürich and you from Olten. How did you two town-dwellers end up in a remote farmhouse?

Armin’s hobby was handiwork, and he wanted a house that he could renovate himself—preferably somewhere in the back of beyond. And so he replied to an advertisement in a newspaper for a teaching job at the secondary school in Oberegg. There was a second applicant, but at the time he was out in the wild in Canada, and so Armin got the job. The Obereggers must have thought it better to have a reformed Zürcher than someone they couldn’t even see. We found this remote old house, built in 1590, and it came with a hectare of woodland. Next to the house there were two huge pear trees. When they blossomed they were like two gigantic bouquets. And when you sat under them, you were deafened by the humming and buzzing of millions of bees.

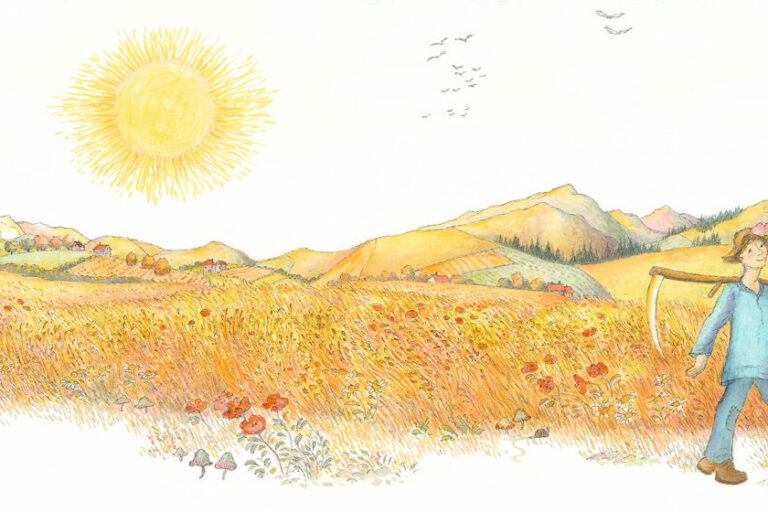

So nature outside your front door made its way into your picture books?

The rabbits that were born in the long grass, the fox that wanted to eat them, and the leaves swirling around in the wind—yes, of course all that found its way into the books. But to start with they weren’t picture books. They were textbooks that I illustrated. The educational publisher Zürich ran a competition for new talent, and I won it. My first commission was pictures of a hedge during each of the four seasons. In those days school textbooks contained pictures that served to get children talking. In fact an artist from Prague who specialized in scientific drawing had been given the job, but she dropped out at the last minute because she’d had to go back to Czechoslovakia to do some work for the government.

…whatever happened I wanted to make this breakthrough into colored picture books.

Käthi Bhend

I’d had no training in scientific drawing, but the publishers commissioned me all the same. We had lots of hedges all around the house, so I kept watching how they grew and flowered, and which fungi or snails they attracted. And I ordered lots of books on nature study. After the publication of this schoolbook I received more letters than I’d ever had in all my life up to then. Schoolchildren wrote things like “Did you do it deliberately or didn’t you know that blackthorn doesn’t flower at the same time as elder?” I wrote back, “I had to show all the plants in flower, but you’re right, it’s wrong.”

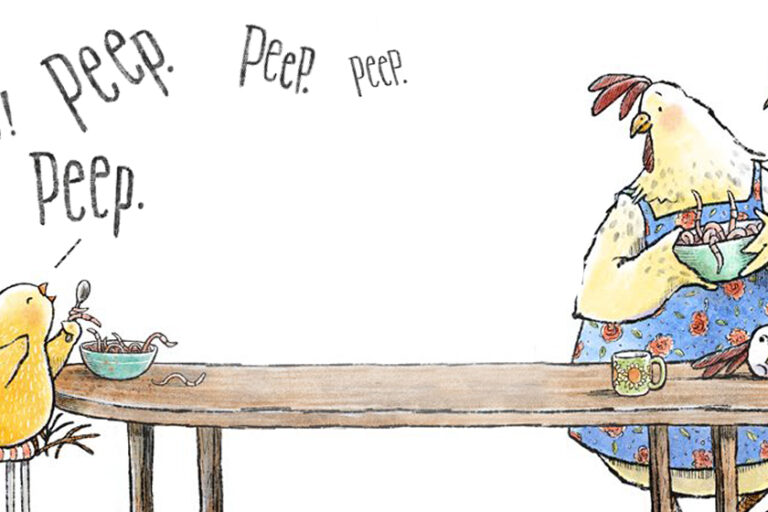

Your most popular book for NordSüd is In My Dreams I Can Fly, with a text by Eveline Hasler. How did this book come about?

I already knew Eveline Hasler as a writer who worked for Nagel & Kimche—I did black-and-white illustrations for Hanna Johansen’s children books, which they published. But they didn’t publish books with colored pictures. Nobody wanted In My Dreams I Can Fly because they didn’t like the idea of having worms, beetles, and cockroaches as the main characters. But then Eveline Hasler persuaded Ravensburger to take it on. I also thought it was a bit tricky since all the action took place underground. I created every picture with a different color background, and the rest is also mega-kitschy, with them knitting or wearing caps—and the grub wears a pair of glasses because he can’t see anything otherwise. The worms weren’t exactly easy either. But I had it all done in three months, having worked day and night because whatever happened I wanted to make this breakthrough into colored picture books. I was ready just in time for the book to be presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair. Without a deadline I’d never have got it done anyway because I’d have continued to work on it forever.