Simply Bernadette

Interview with Bernadette Watts, illustrator of countless fairy tales, classics, and original stories

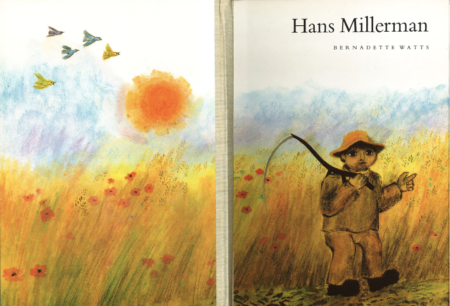

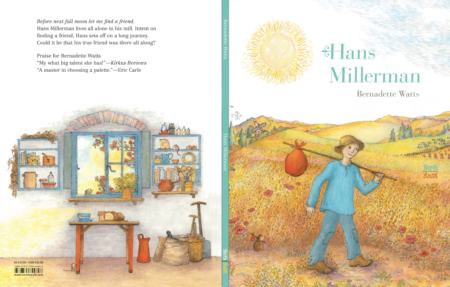

NorthSouth’s parent company NordSüd Verlag has worked with Bernadette Watts for over 50 years, publishing beautifully illustrated stories from The Brothers’ Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, and her own imagination. To celebrate her 80th birthday, NorthSouth has redesigned some of her most beloved original books, Hans Millerman, The Smallest Snowflake, and Varenka. Many of her titles can be found in The Bernadette Watts Collection. In this interview with Pascale Blatter, Bernadette narrates why she is known in Germany only as Bernadette and the inspiration behind two of her original stories, Varenka and The Smallest Snowflake.

Bernadette Watts, during the 1970s, you became a star under your first name. Was that a marketing ploy?

I can’t remember the reason. Perhaps the publisher thought that the books would be easier to sell? I was one of NordSüd’s earliest illustrators; and out of the small circle, which included Štěpán Zavřel, Max Velthuijs, Eleonore Schmid, and me, I was the youngest. The publisher, Dimitrije Sidjanski, always called me “kid.” Maybe that’s why I was also just “Bernadette”?

You were born in Northampton in 1942. What memories do you associate with your childhood there?

When I was a small child, my family left Northampton and moved south to Kent, then known as the “Garden of England.” We lived in beautiful countryside, most of which was the remains of a huge estate that dated from the eighteenth century. My brother, Sam, and I built tree houses and camps out of branches and bracken. On some days a local gentleman would come wandering by and would comment on our camp. He never asked why we weren’t wearing coats or where our parents were. Sam knew his name was Lord Montgomery. Years later we learned that he was Field Marshal Montgomery of Alamein [a senior British army officer who served in both World Wars].

Sometimes on holidays my father would take us to a café where there were cakes laid out on a three-tier china stand. And we went to secondhand bookshops, and I’d go home with armfuls of children’s books illustrated by Edmund Dulac, Arthur Rackham, or Anne Anderson. The illustrations were colored plates or black-and-white drawings that I would carefully color in at home. During these years I already loved writing and drawing, and I was never bored. I actually wanted to be a novelist!

So why did you become an illustrator?

Becoming a novelist turned out to be more difficult than I’d thought. When I left school, I got a job in a library, sticking labels in books. One day I was handed a pile of picture books for children. That was in 1961, and it was the first time I’d seen this form of picture book. One was by Hans Fischer, with a picture of The Seven Ravens on the front cover. I was fascinated—until my boss broke the magic spell: “Bernadette, you’re not paid to look at the books!” A few days later I handed in my notice, applied for a place at the local art college to do a three-year course in book design and production, and was accepted. We only had drawing lessons for half a day a week, given by teachers such as Brian Wildsmith and William Stobbs. After I completed the book design course I studied for a further year in the fine art department. My tutor for drawing was none other than David Hockney. He’d come straight from the Royal College of Art, and presumably needed the money. He had bright yellow hair, big round glasses; and in cold weather he wore shocking pink earmuffs. He was always kind and smiled a lot.

What was your first book project?

After leaving art college I went to London, regularly visiting publishers in the hope of getting work. Eventually I found Dobson Books on Kensington Church Street: a tall, elegant but ramshackle house. The publishers, Dennis and Margaret Dobson, commissioned me to illustrate Rhoda Power’s Stories from Everywhere. I was given an advance of £50. A fortune! Before going home I went straight to an Italian restaurant on the corner of Church Street and had a sumptuous meal. I was sick on the train home.

Dennis and Margaret Hobson offered me a room in their house for the period I’d need to complete the project. I loved the attic, which was the first ever room of my own. It had a view through the treetops of the Round Pond in Kensington Gardens. I was very happy there.

How did you end up with NordSüd?

I got to know Dimitrije Sidjanski through Dobson Books. He was an imposing man, and he wore a white-spotted red head scarf knotted round his head, a bit like a pirate. Soon after that, in autumn 1967, I heard about a world book fair that was going to be held in Frankfurt. I only had enough money for the outward journey. I was hoping that I’d find a publisher for my Red Riding Hood and that I’d be given an advance for my fare home. As I trailed around the fair, one stand really stood out because it was covered with illustrations. I asked to see the publisher, but he was busy. I persisted and returned to the stand six times. He recognized me, looked through my portfolio, and invited me to come to Switzerland.

I think through my ideas, right down to the small details, before I actually start.

Bernadette Watts

How did Little Red Riding Hood come about?

After the Dobson attic I lived in a basement flat in London. I had shown the first Red Riding Hood pictures to Dimitrije and then, in December, I went to Zürich. They asked me to complete the book, and it was published in spring 1968.

There was a lovely art shop nearby, but I only had enough money to buy one sheet of illustration board at a time. I couldn’t afford to spoil it, and so I took great care not to make any mistakes. Illustration board was wonderful to work on. I don’t think it even exists today. I’ve been using watercolor paper for a long time now. But I still hate to make mistakes. It’s not the mistakes that bother me but the waste of paper! I used to start by drawing the picture very lightly with brown felt-tips, and then came oil crayons, and finally on top of that some gouache for the detailed work. Reviewers often say my pictures are watercolors, but that’s wrong. I’ve never used watercolors.

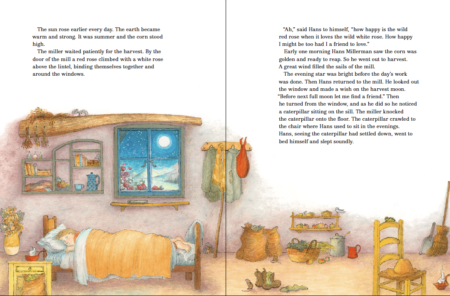

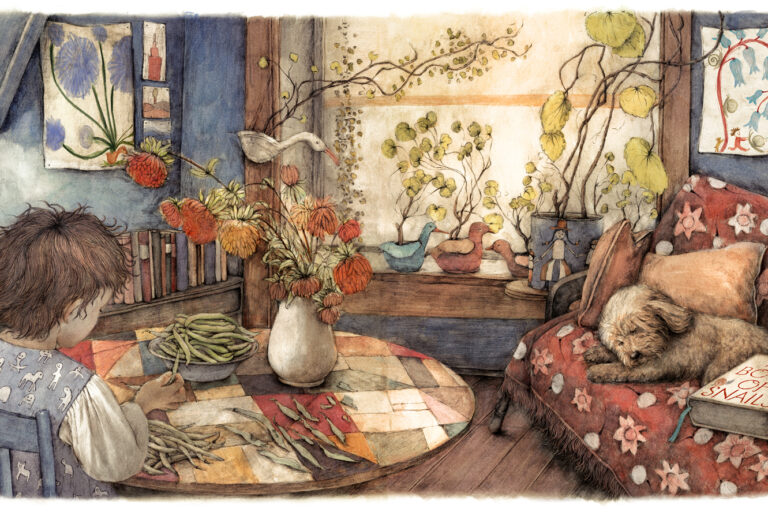

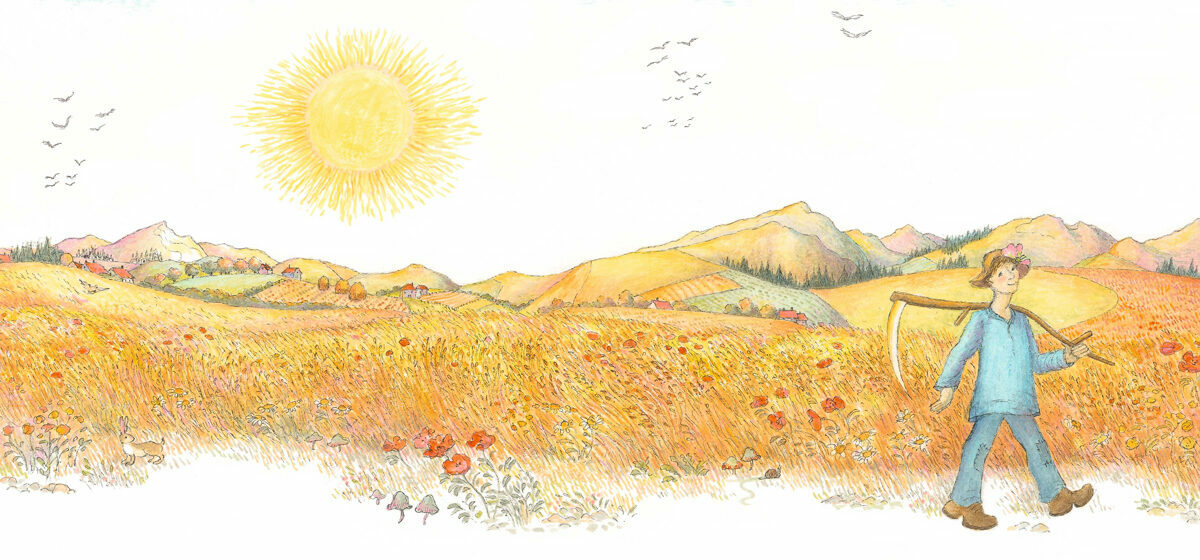

In your early picture books plants play an important role. They shine like fire, attract, protect, and sometimes take over the whole scene. What’s the origin of this pictorial language?

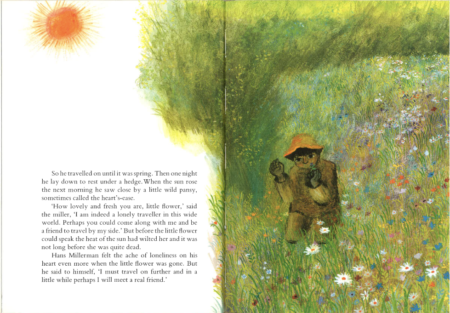

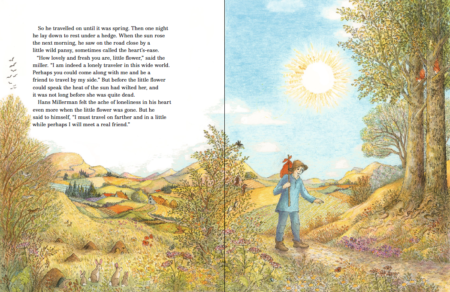

I love all things that grow: trees, flowers, mosses, and especially ferns. My images of flowering fields must be rooted in childhood memories. And I spend the first hours of the day, and often the last hours too, working in my garden.

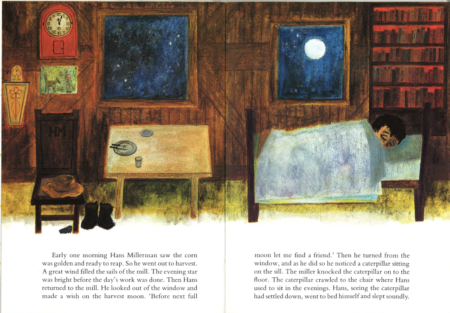

Moon, stars, and twilight play a major role in a lot of your books. Do you often work at night?

During the early days at NordSüd, Dimitrije Sidjanski asked us six illustrators for a night scene in every book—romantic, with moon and stars. From a design point of view night scenes endow a book with contrast. When my son was small, I had no choice but to work at night, which I did for several years. I also like to sit by the window, watching the night sky sink away and the morning clouds and sunbeams coming to take its place. I’m an early riser, as I enjoy that quiet time. I think through my ideas, right down to the small details, before I actually start.

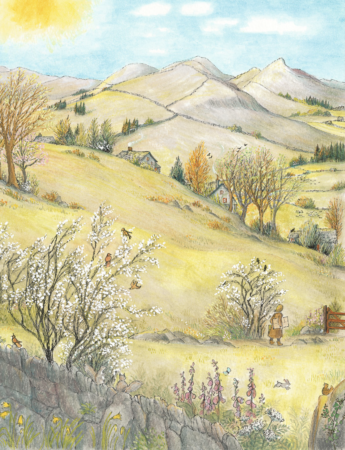

The Smallest Snowflake ends with a picture of a woman with a portfolio of drawings under her arm, walking toward a gate in a beautiful hilly landscape. Is that you?

Snowflake is my most autobiographical picture book. The cottage is a portrait of my house in North Wales at the foot of Snowdon. I lived there for four years, at the beginning of my career as an illustrator. It was the home I loved best. On the kitchen table inside the house are the drawings for Red Riding Hood, though in fact they were done earlier. So yes, the woman in the final picture is me. But I’m not carrying a portfolio—it’s a flat parcel with my finished book. I’m on my way to the post office, to send it to Zürich.

Why did you leave [the cottage in North Wales]?

I gave birth to a son, Bernard, and after the birth I was very ill. I spent five months in hospital, and then it seemed to me impossible to take a baby back to that isolated cottage. I didn’t have a car and went everywhere on foot. And so I moved back to London. My baby and I were homeless for a year. We slept in all kinds of places—even the crypt at St. Martins. Then my father got us a caravan in Kent. I started to work again and wrote to Brigitte Sidjanski. She said she’d been holding two years’ worth of royalties for me because she didn’t know where I was. With that money I was able to buy a small cottage in Kent.

Before that you created Varenka. This book stands out like a monolith in the landscape: the snow-covered house, the soldiers, the iconic style of the painting. When I was a child, I think I looked at that book more often than at any other. I really loved it. How did you come to create it?

Varenka was the second picture book with my own text. The pictures are oil crayon washed with white spirit and gouache on top. Dimitrije Sidjanski asked me to change the big eyes to normal size, but I refused. I still get letters from people who love Varenka and Hans Millerman.

You’ve illustrated several of your books a second time. Why do you do that?

Because I know I can do it even better now.

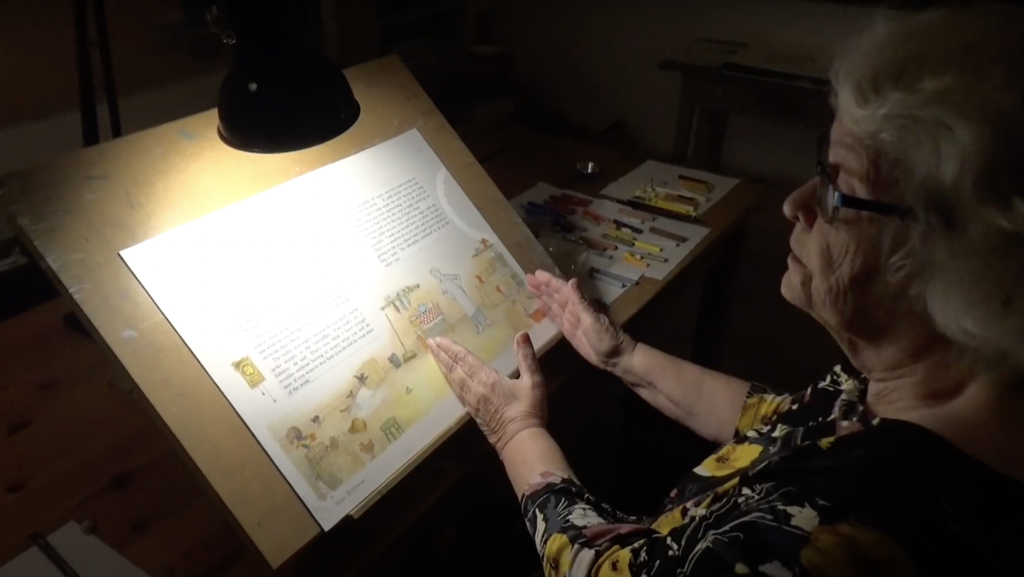

NordSüd’s publisher Herwig Bitsche also asked Bernadette why she decided to re-illustrate Hans Millerman on the eve of her 80th birthday.

I often thought I could improve on some of the illustrations, and some were too dark, and some too much like scribble. But my schedule of work never gave me time to think about improving the pictures. Meanwhile I was always happy with the text. Then came the Pandemic, it arrived in England March 2020 and I was classed as a vulnerable person.

I had nothing to do. And I hated being isolated. So here was my chance. I worked every morning on totally new pictures for this story. In the afternoons I went for a solitary walk or did some gardening. Without my work I believe my spirit would have been broken. After 3 months we were given some freedom. And at the same time finished the set of new pictures.