Constant Inspiration, Endless Studies, Inexhaustible Curiosity

Interview with Polish illustrator Józef Wilkoń

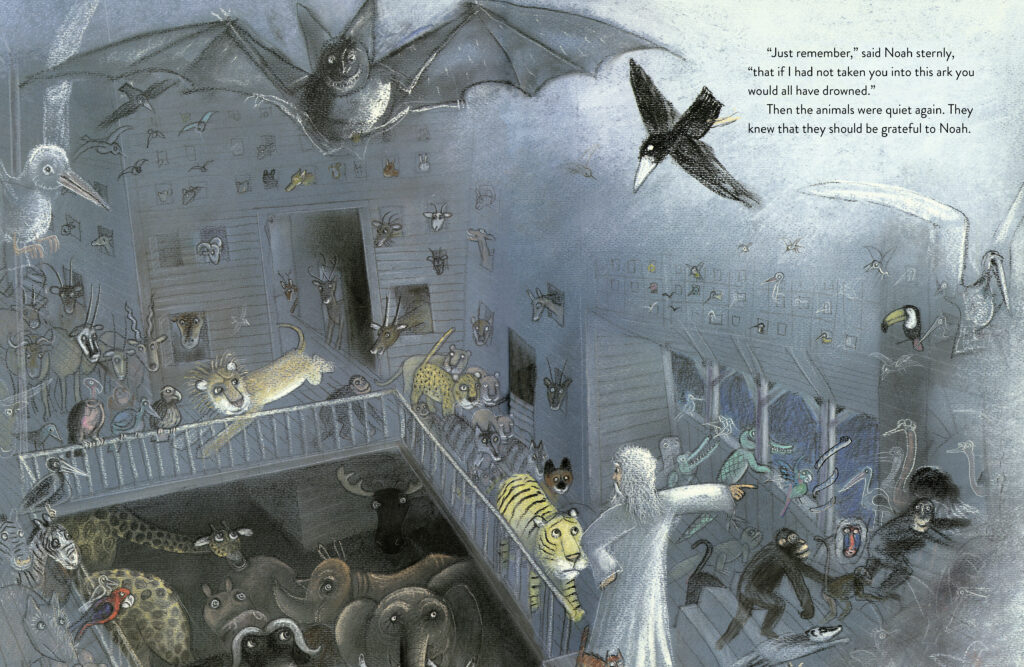

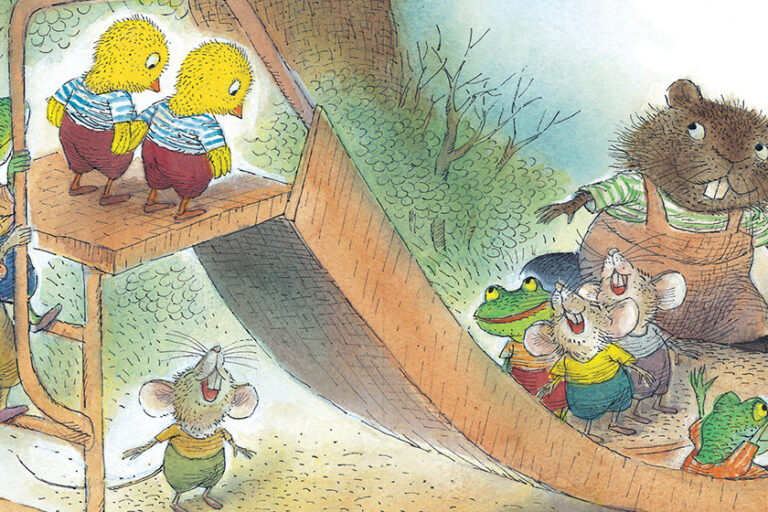

Józef Wilkoń is the king of modern Polish children’s books. His graphic ink, watercolor and pastel animals saturate the pages of such books as The Little Wolves and Noah’s Ark. As German jounalist Pascal Blatter describes Wilkoń, “He lives in a dark wooden house on the outskirts of Warsaw, surrounded by a paradisiacal garden full of trees and animals. Also there, standing in an open shed, are wooden statues… which he made with an electric saw. They touch the souls of all who pass by.” In this interview, conducted by Blatter, Józef discusses growing up during World War II, the curiosity that drives his artistic styles, and the influence of nature on his stories for children.

Józef, let’s begin right at the beginning.

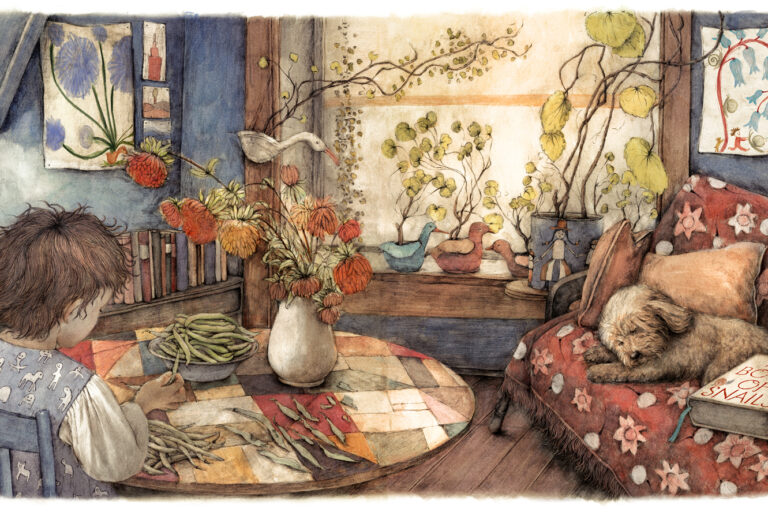

In the beginning, there was darkness. And the spirit moved upon the face of the waters. That’s what it says in the Bible. I studied painting and art history at the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow. To work on my final thesis, I spent the summer in Łańcut, a little town in the Carpathian Mountains where my parents had rented a cottage with a garden and my grandparents lived on a small farm. There I studied nature and all the animals: chickens, dogs, cats, horses, goats, cows, and especially peacocks.

You were born in Łańcut. What was your experience of childhood and growing up in the shadow of the Second World War?

My father worked for the Resistance and was rarely at home, and my eldest brother was a partisan and lived in the forest. I was still a child when the war broke out, but I was also a human being and had to help. We were kept busy hiding Jews in our home. I constantly had to take Jewish families to new hiding places because these had to be frequently changed for the sake of security. Once I took a mother and her children along the river because we couldn’t be seen from the road. I let them do the last stretch on their own. Two minutes after I’d turned round and left them, a Gestapo officer approached me and wanted to know what I was doing all alone in this godforsaken place. . . .

At the same time, my childhood was shaped by the games we played in the midst of nature. A piece of wood and some metal tied to our shoes became our skates. And we made our own skis too. We had the most beautiful winters. In the summer we played a kind of improvised golf and football out in a big field that a hundred cows shared with twenty children. The cows grazed, and we played. The field is now full of new houses, but there’s nowhere for children to play.

When you were a child, what inspired you to start drawing?

My father spent all his spare time at the easel. Painting was his hobby, and he couldn’t imagine living without it. My sister, who later became a botanist, was busy studying nature even when she was a child. Our art teacher at primary school, Roman Kozioł, used to say to me things such as “Don’t bother with straight lines—crooked lines are beautiful!” Or “Forget about your eraser—then you can see where you are and what mistakes you make.” That was the environment I grew up in. Many years later, at art school, I realized just how wise were the words of my first art teacher. In middle school I had a wonderful teacher of Polish language and literature—his name was Jan Klimczyk. I regard myself as born lucky because my life was blessed with so many great teachers. And also because my whole family survived the war, which was amazingly lucky too.

How would you describe the essence of your art?

My work has its origins in painting, and it demands constant inspiration, endless studies, and inexhaustible curiosity. As a result, my studio is always on the move. There are big brushes and little brushes, all kinds of paints, Indian ink, and watercolors. Early on I dived so deep into water that I nearly drowned. “Enough!” I said, and I began to work with harder things such as tempera, acrylics, and oil. I wanted to show that hard was also beautiful. Then in the grocer’s shop I discovered an irregular beige wrapping paper that was filled with large quantities of sugar. Pictures painted on that had a texture like tapestry weave. I’ve never stopped changing and experimenting with my techniques and materials.

My work has its origins in painting, and it demands constant inspiration, endless studies, and inexhaustible curiosity.

Józef Wilkoń

There was a period when you used gold. What does gold paint mean for you?

Gold can look dark or very light, according to which way you hold the book. That corresponds to my view of art. People often say my work is so friendly, romantic, warm. But that’s only one side of it. My animals, for example, are not simply cute. I might draw a fish eating another fish. I saw this scene once in a fossil. It was an explosive moment—captured in stone. And I don’t like it at all when picture books are infantile. In Poland, for example, it was always quite normal for great authors also to write texts for picture books. But in the German-speaking world that was far from what was done. And so in those days I started sketching the basic idea for my books and then suggesting that authors such as Max Bolliger and Eveline Hasler should write the final version of the text. But I often wrote the texts myself. My son Piotr also contributed stories.

It was in 1981 that the close association with NordSüd began. You’ve created twenty-four books for NordSüd, three of them with texts by the founder of the company, Dimitrije Sidjanski. How did this collaboration, late in your career but highly significant, begin?

By then I was actually well known in the German-speaking world and was doing work for Middelhauve, Parabel, Bohem, Patmos, and others. I found my way to NordSüd through Davy Sidjanski, who had just become director of the company and contacted me himself. His father had retired from the business side of the firm to devote himself to writing, but his mother was still working as an editor. I can see them all now: Davy, Dimitrije, Brigitte. It was a fantastic time! Brigitte edited my texts and pictures, we faxed the sketches to and fro, and Brigitte would often say to me, “Józef, Józef, don’t forget we’re making children’s books!” To which I would reply, “Yes, but I’m an artist!” But we always reached a compromise. Because there was lots of latitude, and the work was fueled by friendship. The Brave Little Kittens was Davy’s favorite book, and he launched it with fifty thousand copies in three different languages. Unfortunately, though, it was not my most successful book for NordSüd. But I shall never forget the enthusiasm that lit up Davy’s eyes. I often went to Mönchaltorf with my wife, Małgosia, who used to drive me to Switzerland and also to book fairs. We used to cook together at the Sidjanskis’, and eat, drink, tell stories, and make new plans. Oh, I can still see them all so clearly! What disappears is still here. That was my life.

You created the picture book Mrs. Drosselmann for your wife when she died. It’s about two migratory birds. What messages do the animals carry in your books?

My stories and pictures are rooted in nature and the countryside, and I’m especially fond of the animals. Through them I can show all the problems of us human beings. But not in the style of La Fontaine’s fables, with judgments of good and bad. These are too limited to our human perspective. We humans are not kind enough to nature and animals. In spite of our intelligence and our cleverness, we are stupid. At the time when wolves were being hunted down in Poland, I illustrated three or four books about wolves with texts by Peter Nickl, Binette Schroeder’s husband. Humans must change their mentality. It’s not enough for us to think we are rulers of the world.

The 1992 picture book Noah’s Ark is going to be reissued this year by NordSüd. What does this biblical story mean to you?

I love this book! Later I turned the cover motif into a wooden monument twenty feet high. Today this ark stands beside a lake ten miles outside Warsaw, in the middle of a beautiful landscape. We must learn to love nature. We must realize just how lucky we are that all this exists, and we must protect it.

We must learn to love nature. We must realize just how lucky we are that all this exists, and we must protect it.

Józef Wilkoń

You live in a wooden house, full of nooks and crannies, that you built yourself on the outskirts of Warsaw, surrounded by a huge wild garden filled with trees, pines, and wooden sculptures. Out here in the open air you regularly hold workshops for children, and you and they draw things together. Why do you work not just for but also with children?

I think that all children share a need to paint and draw with us artists. It brings peace of mind and joy to all of us. We can always draw a wolf. Or a fox. It’s very simple, and it’s done in a few moments. That makes us happy. I once stood behind a six-year-old boy who made his brushstrokes with all the infallibility of Picasso. I don’t know what became of the boy, but at that moment he was a great artist.

What do children mean to you?

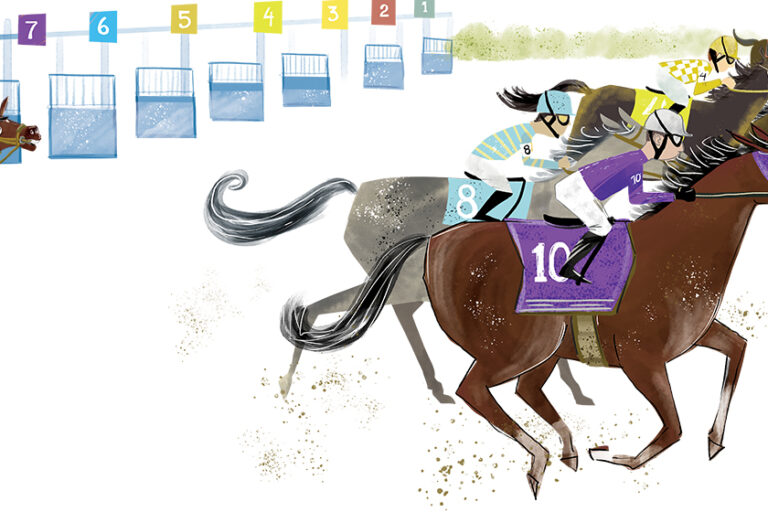

They’re very intelligent—little people with large heads. Everything is already inside these heads. They just need a little time to learn and to gather experience; but they are bursting with fantasy, emotion, and playfulness. Imagine two horses, one young and one old. The beauty of the adult horse lies in the elegance of its movements. During the same period of time that it takes to run its smooth course, the foal will have tried out a thousand forms of expression; its movements are so emotional, exquisite, and varied. The way foals run and jump is incredibly beautiful. It’s possible for every grown-up always to remain just a little childlike. I think a lot of good artists do just that. Being a child is simply so fantastic. That is something we should cherish—it makes us rich.

When do you work?

Best of all I like to work at night, generally from ten till four in the morning. Then everything is quiet. I’m a moonlight painter. But recently I’ve had to sleep at night. My doctor says it’s better for my health. The bat that flits through many of my picture books is a bit like my alter ego.

What are you working on at the moment?

Spring is coming now, and it’s getting warm. I shall take out my chain saw and ax and make some wooden sculptures. I have many strings to my bow, including painting and picture books.

I loved all the tips you have shared, you are right when you said We must learn to love nature. We must realize just how lucky we are that all this exists, and we must protect it.. This article was informative that I can’t wait for your next blog.