A Tribute to Trees

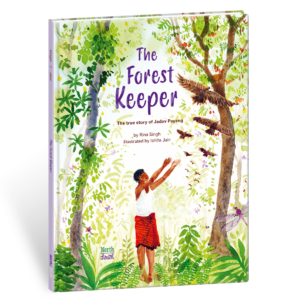

Interview with Rina Singh, author of The Forest Keeper– The true story of Jadav Payeng

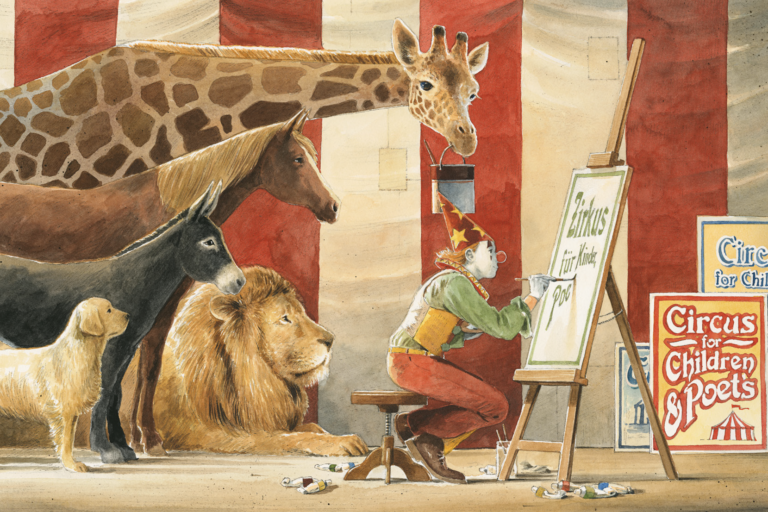

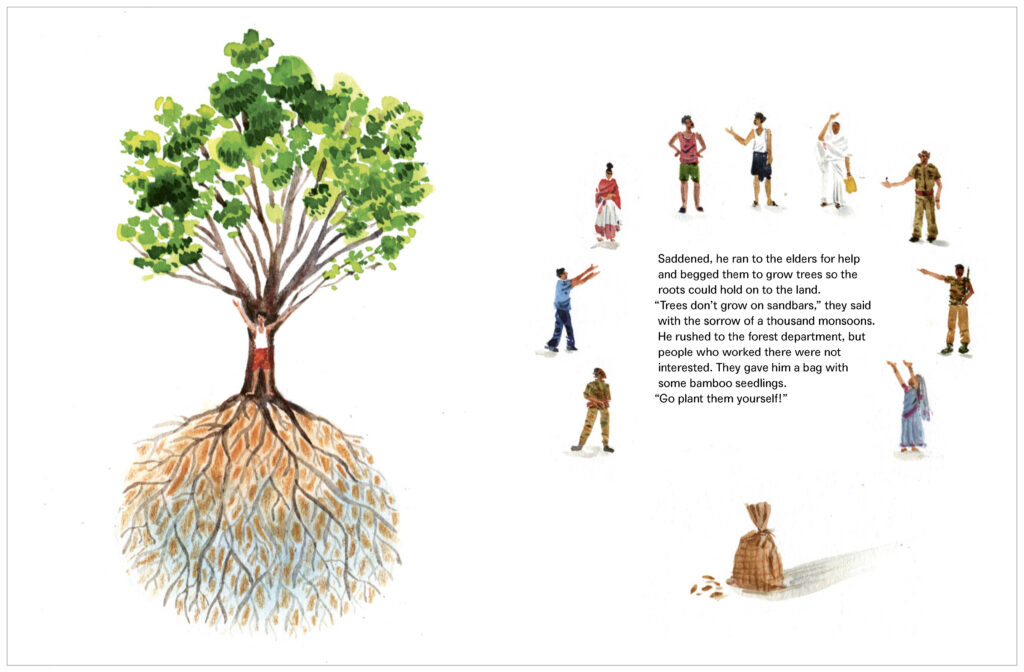

When Jadav Payeng was a child growing up in India, he wanted to make a difference but was dismissed by his elders. Determined to effect change, he planted seeds every day until his small acts grew into a forest. Author Rina Singh also grew up in India. She loved the stories she read in school but her town lacked a public library. Now, she lives in Toronto and writes children’s books inspired by her experiences and passions. Her first book with NorthSouth, The Forest Keeper, illustrated by Ishita Jain, tells Jadav’s remarkable and true story. In this interview, Rina talks about her relationship to nature, why she was drawn to the story of Jadav Payeng, and how readers can make a difference in their own worlds.

What was your immediate reaction when you heard about the story? What were your thoughts? How did it make you feel?

In 2016, I heard about Jadav Payeng almost a year after he was honored with Padma Shri, the fourth-highest civilian award in India. At first, it seemed crazy. How could one man plant a forest single-handedly? Then I watched a documentary about him and started doing further research. I was amazed. Finally, I wrote the story in 2017.

You wrote other picture books set in Indian villages and one about planting trees. Why these settings?

What an interesting question. My father is a celebrated photographer who photographed rural India in black and white. As a child, I accompanied him on these excursions. Maybe at that time, I didn’t understand why he was so fascinated with village life. But as a writer now, I’m so drawn to stories of underrepresented people doing extraordinary things while living in villages with such limited resources. For example, 111 Trees is set in Piplantri, a small village in Rajasthan. When I heard what Sundar, the protagonist, was doing for girls and trees I went to India to meet him. I was blown away by his courage. So many years later, I’m still in touch with him.

Some of our readers live in big cities where you can’t grow a forest. If you can’t grow a forest, are there other ways are there for children to make an impact?

Many people think that there is no nature in the city. That’s not true. The city has the sky, birds, rain, wind, sun, and public parks. Watch the clouds from your window and see how the sky changes color at sunset.

Even the most densely populated skyscraper city has a tree or a patch of grass. Find it. Study it. Play in it.

Maybe there isn’t a forest nearby, but you can ask your family to take a drive to see a forest. When you spend time with these awe-inspiring trees and connect with the natural world, you will understand how important they are to our well-being. So, get outside! Go hiking or camping, have a picnic, or do some bird watching. Hug a tree or climb one if you dare!

Be careful with fire when you are in a forest. Help to prevent wildfires that destroy forests.

When you spend time with these awe-inspiring trees and connect with the natural world, you will understand how important they are to our well-being.

Rina Singh

Another amazing thing you can do is go for an “awe” walk where you live. How do you find awe? You wander mindfully and look around. Count the things that fill you with wonder. Look around and appreciate your surroundings. Have you ever watched pigeons? Squirrels? They are so much fun to watch. Splash in puddles or play in the rain. Bugs, birds, squirrels, and many more critters make their homes in densely urban settings. Count the birds you see, find a bug, and study what it does. My favorite thing is to take pictures with a cell phone when I go for an awe walk. Maybe you can borrow a phone from your parents.

Don’t wait for Earth Day to get some of your friends together and clean up the neighborhood. Most likely adults will join you, and you can teach them a thing or two.

And for now, if you can only read about the trees or watch documentaries, then do that.

Please use paper wisely. We can save trees from being cut down by using less paper.

What is your connection to trees, forest? Are they part of your life?

My first connection to a tree was a neem tree that grew in a public space outside my home in India. We played under it, sat in its shade, and listened to stories from neighbors who often gathered there. But it was after reading The Giving Tree, I saw them in a new light.

I’m so grateful to now live in a home surrounded by trees. The maple tree in my backyard is the first one to turn red in October. I can see the tree from many windows. Every time I look out, it makes me gasp. I also have many tall evergreens, so it looks green even when covered by snow. Just outside my front door, I have a gorgeous magnolia tree. It blossoms for only two weeks. It reminds me of life. We all come into this life for a certain amount of time. And we must also try to do something spectacular to wow the world.

We must also try to do something spectacular to wow the world.

Rina Singh

You define yourself as an Own Voice author. Can you please explain?

Own Voice is a movement that started as a hashtag. Diverse books show us parts of the world we know little of. Reading an Own Voice book means being confident that the world created in the story is authentic. Own Voices authors and illustrators know the cultural nuances because they are active members of that culture. It is not from an observer’s gaze.

In my book Grandmother School, there were certain scenes and situations where the illustrator and the publisher consulted me for cultural inaccuracies and were very appreciative when I suggested changes. For example, there was an image of a young woman with a ponytail drinking chai at a village tea stall. That wouldn’t happen in a village or even a small town in India. Women don’t go out alone. So, we changed that.

In 111 Trees, there was an illustration of young girls running to school, and a couple of them had their hair open. So, I advised the publisher that it wouldn’t happen in a village. The hair must be braided. It was a small cultural detail, but it was necessary. They fixed it.

The books we read are our windows into other experiences. Therefore, ensuring that our view is accurate, informed, and authentic is vital.

Rina Singh

Ishita, who is from India, illustrated The Forest Keeper, and I did not have to worry about the cultural nuances.

Despite knowing the culture, I still do a lot of research, and in case the protagonists are alive, I try to get in touch with them to interview them and spend time getting to know their stories better.

The books we read are our windows into other experiences. Therefore, ensuring that our view is accurate, informed, and authentic is vital.