Through Sonja Danowski’s Eyes

Interview with Sonja Danowski, illustrator of Grandma Lives In a Perfume Village and author/illustrator of Smon, Smon, Little Night Cat, and In the Garden with Flori

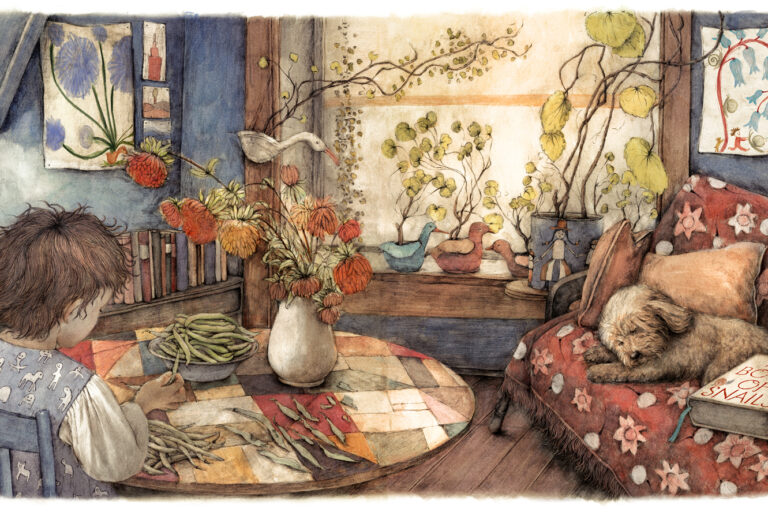

Sonja Danowski was born in Iserlohn, Germany. After finishing her studies in Nürnberg, she went to Berlin to work as an illustrator. Her focus is mainly on picture books and on pictures that preserve human memories. Her colored drawings have won several international awards. Her most recent work is In the Garden with Flori, published as Im Garten mit Flori in Europe. Danowski discusses her artistic studies, her challenges with illustrating nature, and the influences that picture books can have on young readers.

What memories do you have of your own childhood? Are there things that have remained in your head and that your pencils and paintbrushes revive in your current work?

I used to hide little treasures in secret places, and I loved climbing trees, making soup out of dandelions, and jumping down from high walls. I was never afraid of falling and saw no need ever to change my playful way of life. But I still remember how worried I was at the prospect of growing up—or at least by what children imagine being grown up is like. Today I’m incredibly lucky to be able to go back some way into the fantasy microcosm of my childhood when I’m working on my children’s books.

What made you choose illustration as a career? And why have you made picture books the focal point of your work?

I’ve always loved books: Leafing through the pages, studying the letters and pictures, and all the time being drawn further and further into the book in order to discover the world within. I can’t put into words exactly what the attraction is. There’s a kind of magic in the production of a picture book, and it drives me on as well as convinces me that my time has been well invested, no matter how long the work has taken. The whole process is sometimes demanding, but the finished book is then like the pure essence of everything I’ve put into it. Books have a lasting value. They never lose their meaning, and you can read them over and over again as if they were still new. The more I think about it, the clearer it is to me that what I love most is books and their creation.

Which painters and illustrators did you like when you were a child?

When I was learning to walk, I always held onto the bookshelf in the living room, and I grabbed books that were at my eye level. One of those was a little volume of Picasso’s unbelievably beautiful portraits of children. That’s my very first memory of consciously looking at art. I picked up that book over and over again. Child with a Dove had a magical effect on me. A special favorite among my picture books was Eric Carle’s Very Hungry Caterpillar, because of its colors and the intriguing insect holes in the paper. In those days, I still didn’t realize that the pictures had been created by the enchanted hand of an illustrator. They were simply there for me—the very hungry caterpillar and the gorgeous butterfly. And another favorite was a naively illustrated book in which a giant whale got smaller and smaller because it was grieving, and it ended up in an aquarium full of fish. That unhappy whale moved me to tears.

Books have a lasting value. They never lose their meaning, and you can read them over and over again as if they were still new.

Sonja Danowski

During your studies, was there one particular style of illustration that attracted you?

There are several styles that I like very much—for example, naïve illustration, which has become fashionable again in the last few years. There are lots of illustrators whose work I admire. All the same, I’d never be tempted to imitate their style, because their work has already been filtered by their eyes and not mine. What most attracts me is the task of finding my own pictorial language through which I can interpret my personal view of things. For instance, if I draw a tree, I like to study it carefully before I capture it on paper. I want to depict its leaves (unless it’s winter), its trunk and branches, and the birds that are in it—in fact everything that makes it my tree. If beforehand I have to look at how other artists have drawn their trees, so that I can draw mine in similar style, it might well become a beautiful tree, but it won’t be mine.

What in particular do you like about your job, and what don’t you like?

I like the bright light of my workroom, which is also my living room. And I like drawing long into the night. I like thinking things through, and I like working with and for children. I particularly like the fact that my work connects me with other cultures: My pictures and stories travel round the world, and I’ve been able to accompany them. And I also like the fact that there are so many wonderful people engaged in the field of children’s books. As my work is dependent entirely on me alone, creativity is a very emotional exercise. I often find it difficult to take decisions and to cope with my emotional ups and downs, which sometimes hit me like an unforeseen thunderstorm. And then my mind is filled with self-doubt, which almost always blocks any further progress. But as time has gone by, I’ve learned to see this is a spur to improvement. And so I’ve almost learned to like it!

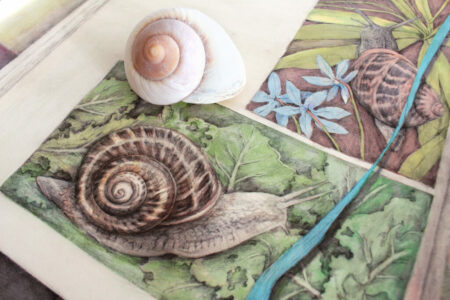

Your illustrations are very realistic. To what extent do you use real models or references?

When I go for walks, I usually take my camera with me in order to take photos of things, like birds, flowers, buildings and so on, which might be of interest for future pictures. I also take home little objects I find on the way, like leaves or stones. A wonderful side effect of this is that I’ve become much more observant of my surroundings.

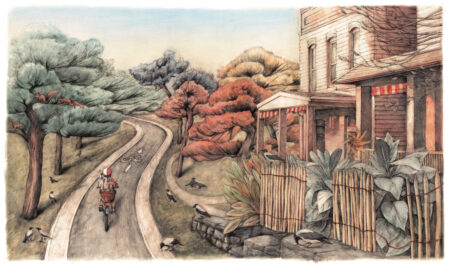

When I discovered my intense passion for drawing, I devoted all my energy to improving my technique. The picture of a plant in which even the tiniest detail was recognizable gave me a genuine feeling of success. But then at some time or another, I no longer felt that this was exciting, and so I began to combine things from my surroundings with images from my own imagination, and that produced scenes which appear to be real but in fact have never happened in reality. For the strangest of all my books, Smon, Smon, which takes place on another planet, I even designed a surreal world, which meant complete freedom from all realistic preconceptions. But depending on the subject, I always have to do some careful research beforehand. To create the illustrations for O. Henry’s short story, The Gift of the Magi, which takes place in New York in 1906, I had to find out what the city looked like at the beginning of the 20th century. And so I studied lots of old photos. What you see in the drawing, though, is always a free interpretation that looks quite different from the photos I used as references. That also applies to pictures of people. With just a few exceptions, the characters in my books are fictional. There’s one book in which my father appears, and another in which I myself function as a reference. That made it much easier to draw the faces from different angles, which is especially difficult with fictional characters. It usually takes me several attempts to get that right.

Another important and typical feature of your work is the lighting. What role does that play in your illustrations?

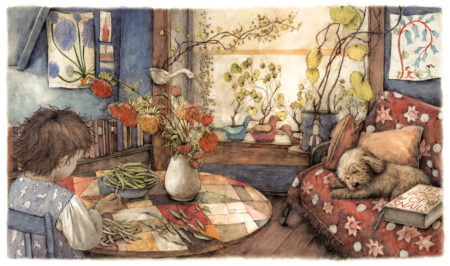

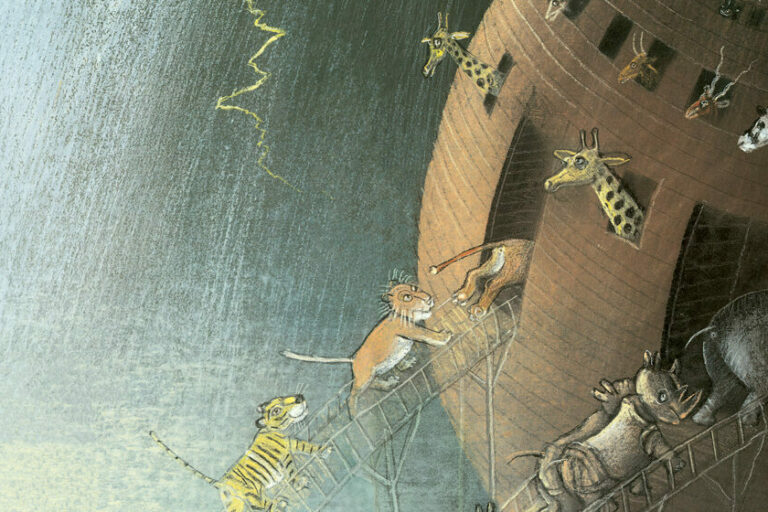

Light is one of the most magical of all the elements of perception. It changes colors, forms, and feelings, and allows objects to shine or to disappear in the dark. When I illustrate a story, I see the whole action like a film unfolding before me. Everything is moving and in three dimensions. In my pictures there are lots of different shades through which I try to create plasticity. The fact that my colors are generally very subdued is the result of my technique but is also a stylistic feature.

First I sketch the composition with a pencil. It takes a while for me to work out precisely how everything should look and how a new motif can emerge from the hatching. Then I color the preliminary drawing with ink and watercolors. These give the drawing a smoother appearance and produce soft transitions between the lines, emphasizing some details while making others part of the background. The coloring denotes the light and the depth of the picture, while the penciled primer produces the atmosphere.

Everyday scenes and small details from everyday life are always very noticeable in your work. What do you find in them? What part does the everyday world play in your creative process and in your work?

I like to include little details so that observers can discover something new every time they look at the picture. The scenes become increasingly concrete but at the same time more mysterious. I especially like decorating interiors, in which we can find clues about the nature of the inhabitants. There are many memories associated with the objects that surround us. I find it really exciting to observe everyday scenes in a picture, because then we look at them much more consciously.

And what role does nature play in your work?

I adore nature—it’s the greatest treasure in the world—so varied, rich and precious that it goes way beyond the power of our imagination. And that makes it very difficult to depict nature on paper. Drawing animals and plants is always a special challenge for me, even those I like best. Until now most of my books have been about people. Humans are pretty dominating, and so when they appear, nature normally takes too much of a backseat, although I always try to give it as much space as possible. In one of my books, The Forever Flowers, the main subject is the winter landscape as a place of yearning. I particularly enjoyed illustrating the brilliant novel The Grass House by the Chinese author Cao Wenxuan. The story takes place in a village in rural China, and I found Cao Wenxuan’s descriptions of nature absolutely inspiring.

What inspires you to do your drawing and designing?

That’s a good question, and I can’t think of any clear answer, which probably shows that it’s mainly a matter of intuition. When I’m looking for a subject, I do get constant inspiration from beautiful sensual impressions: Sounds, music, color schemes, patterns, shapes. But all I actually need for my drawings is a pencil plus some paper and a bit of peace and quiet. Drawing and thinking—they go very well together. The hand moves intuitively across the paper, and it’s only a matter of patience before something nice appears. It’s different, though, with paints. When I’m working with watercolors, I need to concentrate much more. I don’t think of this or that but focus completely on the colors. It’s a bit like doing arithmetic—all I have in my head then is the numbers.

Not every day is the same. Sometimes I feel totally creative and everything flows easily from the hand, whereas at other times I can hardly muster a single decent line.

Why do you like writing your own stories?

I particularly like this way of working. If the story is based on my own ideas, it’s more flexible; even while I’m working on the book, I can always make changes. That happens quite often, and it can be a real challenge to bring the story to a suitable end. I like surprises, and also the ups and downs I experience during the process of creation. And it’s a relief to be free from outside pressures. There’s no deadline, and initially nobody has to like what I’m doing. I never show anything to a publisher until the book is finished, and so I can take as much time as I need.

If we provide today’s children with good literature, they will see the world differently and look towards the future with open-mindedness and tolerance.

Sonja Danowski

What must a story have if it’s to appeal to your heart and make you want to illustrate it?

If a story is entrusted to me, I always feel very honored. For it to appeal to my heart, I have to be moved by whatever message is conveyed by the text. It can be some sensitive description that sparks my imagination or my empathy and draws me into what you might call the soul of the story. It certainly has to appeal to my imagination if I’m to trust myself to complement the text with my pictures in order to enhance the impact of the message. I’m particularly attracted to random flashes of poetry and lovably crazy behavior—things that remind me of my own dreams, fears, and experiences. And I also go for stories that come up with surprising ideas. Some texts already seem to me to be so powerful that I feel they don’t even need any pictures. Sometimes, unfortunately, I have to turn down a moving story simply because I don’t have time to do the job. As my analogue technique is extremely time-consuming, illustrating a single book can take me several months or even years.

In your opinion, what effects can picture books have on young readers?

If we provide today’s children with good literature, they will see the world differently and look towards the future with open-mindedness and tolerance. Every book performs a different function. It can be informative or entertaining or narrative, and each one will conjure up its own visual language. Looking at a book, studying the colors and forms, delving into the aesthetic side of a story—all of that can be a sensual experience. It’s important to offer children as many different styles as possible. With the help of books, we can gain insights into other times and cultures. I wish every child could have access to books, peace, and freedom!