A Well of Vibrant Stories

Interview with Binette Schroeder, author of Mr. Gray and Frieda Frolic and the anthology Binette Schroeder’s Well of Stories

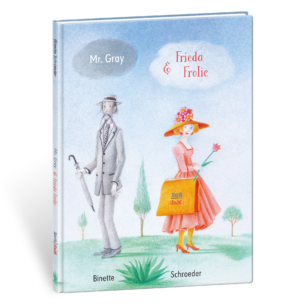

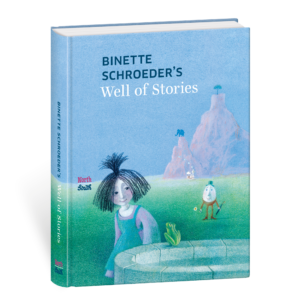

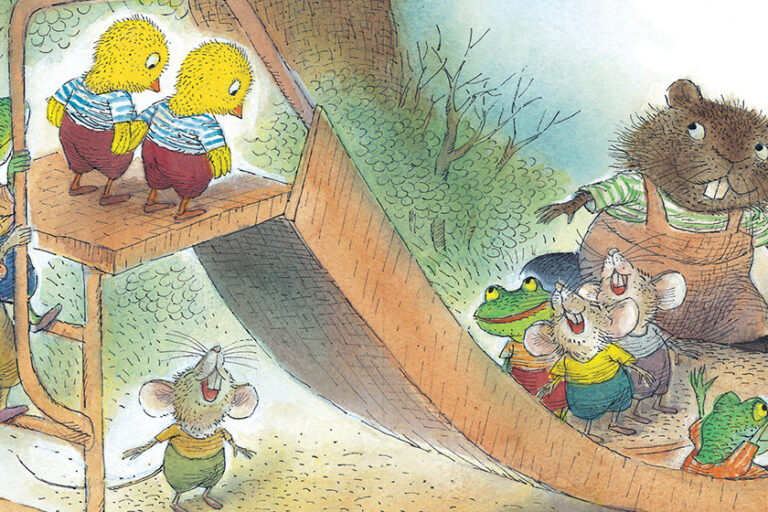

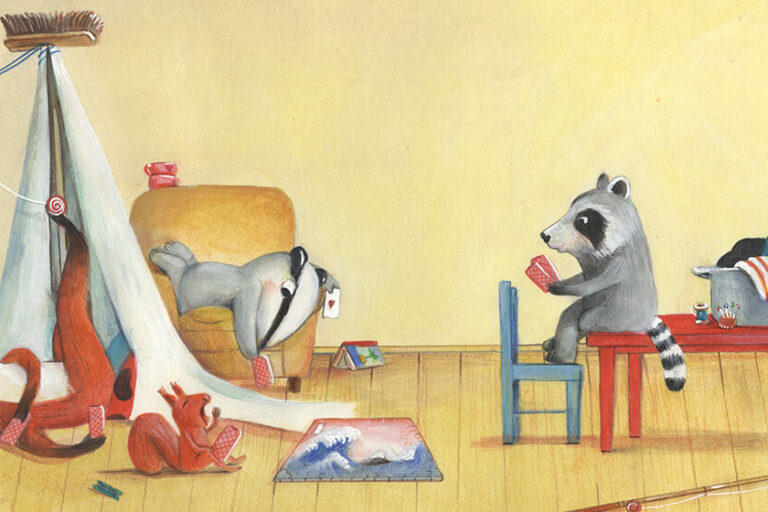

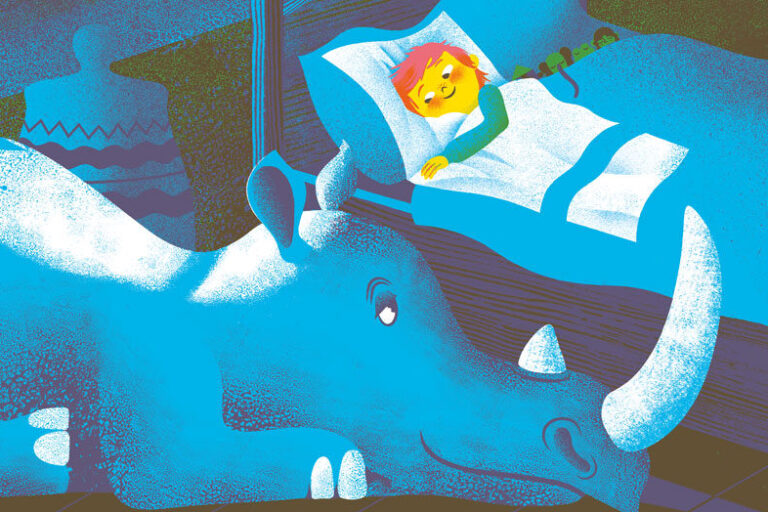

Binette Schroeder has written and illustrated picture books for more than fifty years. Her most recent title, Mr. Gray and Frieda Frolic, published in 2021 as Herr Grau & Frieda Fröhlich by NordSüd Verlag, tells the story of an unlikely couple with humor and charm, showing us what we gain when we open ourselves to chance and let color into our lives. Many of her other titles, including Flora’s Magic House, The Frog Prince, and Laura (all mentioned below) appear in Binette Schroeder’s Well of Stories collection. This interview with Binette about her experiences in publishing and the inspirations behind her characters and imagery was conducted by Pascale Blatter for NordSüd’s 60th anniversary.

How did your first book, Flora’s Magic House, come to be published by NordSüd?

In 1968 I was a newly qualified graphic artist with a huge portfolio under my arm, traipsing through the Frankfurt Book Fair in search of a publisher for my first complete picture book, Archibald and His Little Red. In the portfolio there were also two gouaches that didn’t yet belong to any story.

I had a long list of the most important children’s publishers, and simply went from stand to stand. People just glanced at my illustrations, muttered “quite nice,” and said I could send them and they’d let me know after two or three months. I wasn’t very happy about that. I’d have preferred a clear yes or no on the spot.

The last name on my list was NordSüd. Sitting there was a very good-looking, elderly man with streaks of gray in his hair, an Errol Flynn–style mustache, and bright blue eyes: Dimitrije Sidjanski.

The walls of his tiny stand were lined with strips of black material, and there were original, framed illustrations hanging on them.

This publisher spoke German with a Slavonic accent, and he said, “I’ve got ten authors and ten illustrators, so I don’t need any more—but . . . show me all the same!” He had a look at Archibald but wasn’t particularly keen. On the other hand, he really liked my two gouaches. He asked about the story, and I explained that there wasn’t one yet. He replied, “Go home, write a story, and come again tomorrow morning. If I like the story, I’ll give you a first option.” My friend Ursuline, with whom I was living in Frankfurt, explained later that a first option was a preliminary step toward a contract.

So back at Ursuline’s, I sat down straightaway at the desk and—I really don’t know how it happened—all of a sudden I had a story to go with these two illustrations. Ursuline typed out a fair copy. At about 4 a.m. the two of us fell into bed exhausted. Punctually at 9 a.m. I was back at the fair. Dimitrije read the text and simply said, “I like it. I’ll give you a first option.” And that’s how Flora’s Magic House, [Lupinchen in Germany] came to be published by NordSüd.

Why did you paint the first two Flora’s Magic House pictures in the first place?

These two pictures—Dimitrije was the only person at the Book Fair to show any interest—actually had a very special motivation: I was lovesick. On the most beautiful spring day, a love affair had just come to an end. In my little flat in Berlin, I closed all the curtains and threw myself in sheer misery onto my bed. Then suddenly in my mind’s eye I saw this picture. It was like a slide being shown behind my eyelids. I looked at it for a long time, then I jumped up and painted it. After that I lay down again, and before long the second picture appeared. These two images came from my innermost depths, without any planning or concept, and yet eventually they became the first two illustrations in my picture book. As far as I’m concerned, Flora’s Magic House is not only my most successful book, but to this day it’s also the most important.

It was like a slide being shown behind my eyelids.

Binette Schroeder

Flora’s Magic House was published in 1969. Things moved very fast from “first option” to a contract. A lifelong connection grew out of this start, so what actually happened?

In order to get the contract for my first book, I drove my little VW from Berlin to Mönchaltorf. The publishing company and the family were in the same house. Brigitte Sidjanski gave me a warm welcome, and I felt at ease straightaway. I really liked her powerful voice and her deep, dark laugh. We did our negotiating in the living room, at a low glass table. Brigitte served us tea and biscuits. Tarka, their Afghan hound, joined us and sat on the sofa like a grande dame, with her hind legs elegantly crossed. When we’d finished the discussion, Brigitte and Dimitrije left the room to draw up the contract. So I was left sitting alone at the table with Tarka. Suddenly she stretched out her long neck, and her delicate snout was heading straight for the pot of cream. I shouted, “No, Tarka!” She simply uttered a soft but menacing growl and calmly proceeded to empty the whole pot with the utmost relish.

Right from the start I felt at home with NordSüd. It was all very informal, but also out of the ordinary—in fact very special.

You went to Frankfurt to seek your fortune as an illustrator, and you found it. Since 1964 there’s been the International Children’s Book Fair in Bologna, which you’ve also visited regularly. What memories do you associate with Bologna?

I’ve always enjoyed the Bologna Book Fair, and I remember the time when it took place in an old Italian palazzo in the center of the city instead of the exhibition center, where it’s held today. Those really were legendary times! There was a wonderful buzz in the world of children’s books, and Bologna was its epitome. They’d laid out a buffet at the fair, set out on a table that didn’t seem to have an end, and it was covered with the most amazing dishes. We felt completely at ease with Italian gastronomy, and it was as if we were one big happy family—the European team of children’s book makers.

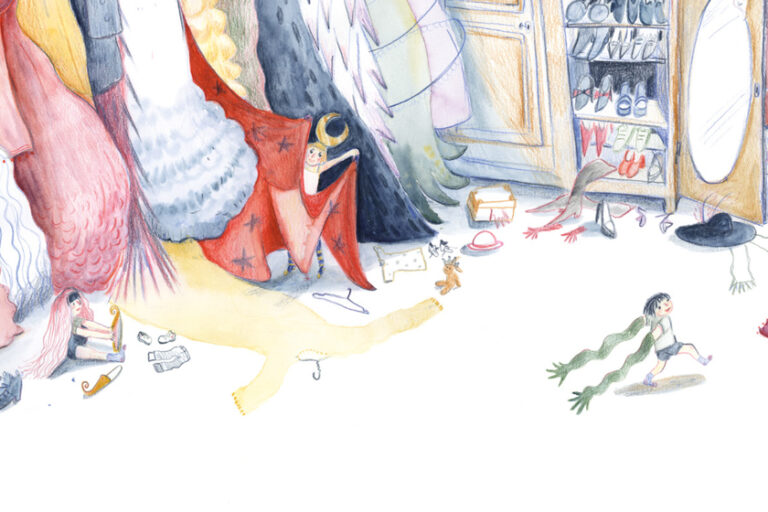

One of your trademarks is a colorful turban, and even today you often wear shoes of different colors. Your mother was a costume designer, and the theater also appears in some of your compositions. In fact, your books often combine scenery like an enclosed stage set, with these bright, almost dreamlike colors. How did you develop the technique for this style?

I was strongly influenced by my training at the Basel School for Design. It developed logically from the sound base we were given in our drawing courses. During the first year, we were only allowed to work in black and white. Then very gradually and cautiously we moved into color via different shades of gray: gray green, gray blue, a yellowish or reddish gray. That helped me to develop a very refined sense for all the potential variations of each color.

Later in my career, colorful backgrounds took on a central role in my work. I’d developed a technique of my own to create the effects of transparency and clarity. I used special paper that I laid in water and took out again after a short time. Then I used a piece of soft cloth to rub the paint very gently onto the paper. That’s how I created this special effect of vivid coloring. Today I very rarely use opaque white. For very bright spots—such as the glint in someone’s eye—I use a razor blade and very carefully scrape it out of the paper. I’ve got an American friend who’s also a painter, and when I asked her to try it, she was horrified. “But I’m not a scratcher! I’m a painter!”

The paper I used doesn’t exist now. Most of the time I use pastel crayons and colored pencils.

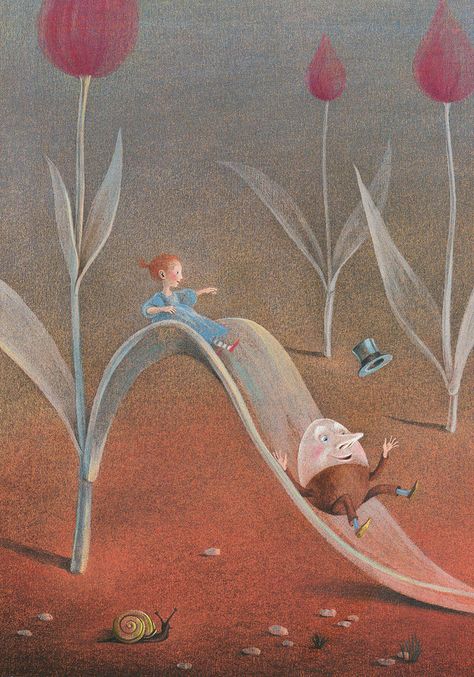

In your book Laura, and also in Flora’s Magic House, the egg-shaped Humpty Dumpty makes an appearance. What role does he play in your work?

In the Anglo-Saxon world of children’s books, Humpty Dumpty is a well-known character. He’s a kind of oblique reference to my wonderful American grandmother on my father’s side. She came from a Jewish family that ran a textile business in Baltimore, and she managed to survive the Second World War in Hamburg only because obviously nobody knew about her Jewish origin—or if they did, they kept quiet about it.

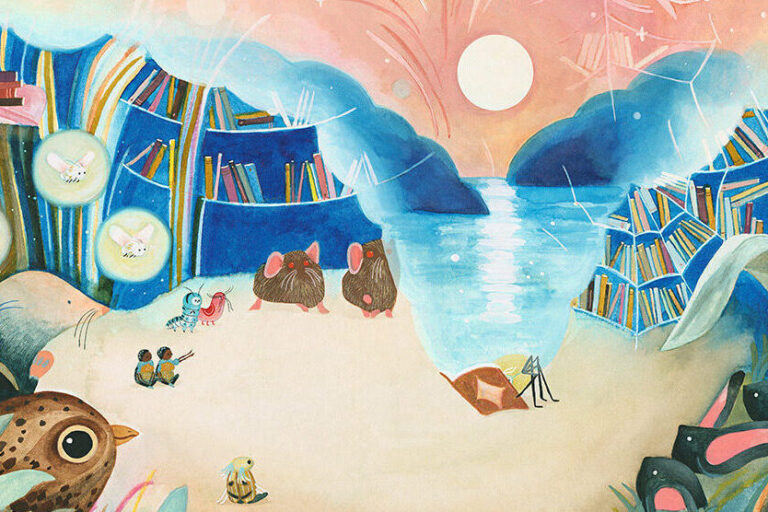

For me as a child, my grandfather’s house in Hamburg was a self-contained universe of its own. He was an international businessman. He’d traveled the world, and he was extremely cultured. His library was a magical cosmos, and he introduced me to it himself—though of course I was never allowed even to hold any of his precious books. I’d sit on his knee, and he’d show me pictures by Pieter Bruegel and Hieronymus Bosch. I was absolutely entranced by them. Those early impressions have had a huge influence on my work. Many of the recurrent features of my own pictures have their roots in my grandparents’ house.

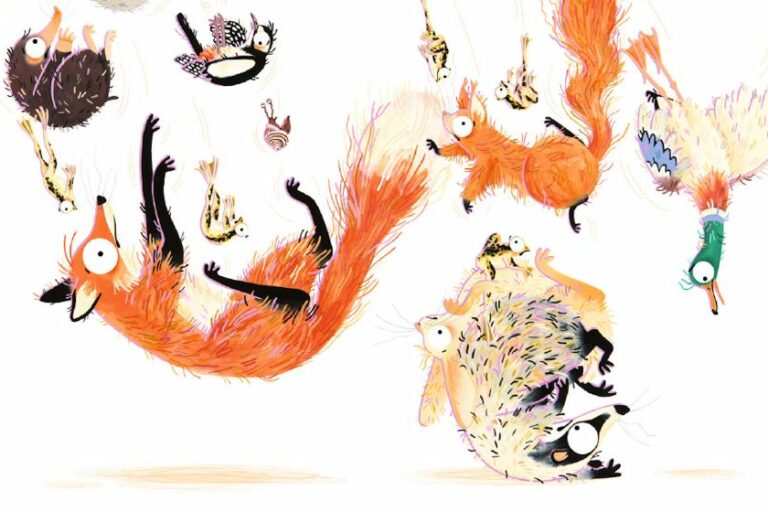

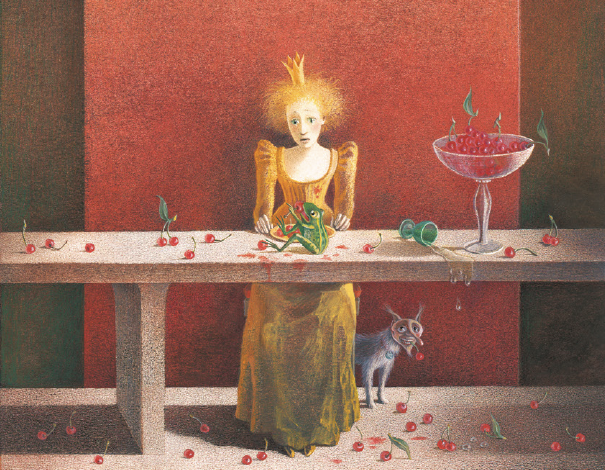

Your pictorial language is often reminiscent of surrealism—from the cool avenues of a Giorgio de Chirico to the soft watches of a Salvador Dalí. In your Frog Prince of 1989, there’s a dog with a human face. What’s your connection with surrealism?

The link is very marked. You’ll find loads of surrealist elements in my paintings: stones, plants, and hills with faces; trees wearing trousers and shoes; tables with animal legs. As I said, my early influences were the worlds of Bosch and Bruegel. Even in everyday life I’ve trained my eye for the surreal. I’m sure I register a lot of it unconsciously, and afterward I can no longer remember exactly where it came from. But the dog in The Frog Prince is a very concrete example. It’s a deliberate homage to my friend and colleague Klaus Ensikat, whom I admire enormously. The dog’s collar has the initials K. E. on it.

Unquestionably, though, my surrealist roots are in nature. I firmly believe that nature and surrealism are somehow related. Nature’s imagination knows no bounds, and it exceeds the wildest fantasies of us humans. Surrealism does the same in its own particular way. I’ve always imagined nature as being inhabited by strange beings—for example, when I was a child, I was convinced that elves were real, and I used to look for the entrances to their homes in the roots of old trees.

When did you first realize that you wanted to be an illustrator?

When I was just ten, I knew that I wanted to make children’s books. At primary school I wrote short stories and illustrated them. They were usually inspired by fairy tales or the Bible. Though I have to admit that a little later I decided I wanted to be a nun and with my veil flying in the wind, ride a white horse alongside a stormy sea!

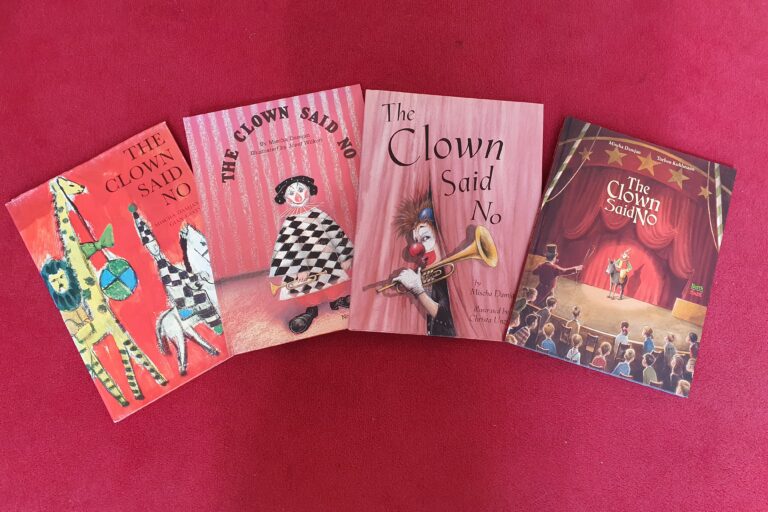

But I became an illustrator after all. And my very first picture book, Archibald, which Dimitrije Sidjanski had rejected, has actually now been published by NordSüd. It’s part of a comprehensive collection of my works that Herwig Bitsche published in 2019 to celebrate my eightieth birthday. It’s called Bilderbuch-Brunnen, [Well of Stories].